The Senegal Chameleon, Chamaeleo (Chamaeleo) senegalensis

By Kristina Francis

Citation:

Francis, K. (2008). The Senegal Chameleon, Chamaeleo (Chamaeleo) senegalensis. Chameleons! Online E-Zine, February 2008. (http://www.chameleonnews.com/08FebFrancis.html)

All photos courtesy of author unless otherwise stated.

The small but voracious Chamaeleo senegalensis is endemic to Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cote d 'Ivoire (Ivory Coast), Gambia,Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Togo. Think of it as pest control without borders, a nimble sharpshooter with a bottomless pit for a stomach. The usual image chameleon enthusiasts have of this species is a small, drab, stress-spotted animal moping in a pet shop. It is time this species was appreciated for its true beauty, a far cry from the common concept.

Most casual pet owners and serious keepers alike have seen the ubiquitous Senegal chameleon in pet shops and markets around the world. The only nations legally exporting senegalensis, according to CITES, are Ethiopia, Benin, and Togo. The species' hardiness and appeal only works against them; they are common in the wild, inexpensive as imports, and often the cheapest adult true chameleon on the market. Because they are so cheap, even immense losses do not hurt the profit margin, so there is no incentive to handle them carefully during the import process. By the time they are found withering in pet shops, they are contending with stress-induced parasite blooms and illness. The best bet for keeping or breeding Senegals successfully is to purchase captive hatched (the species is not often captive bred) from a dealer. If they cannot be found, wild-caught juveniles can be cleaned and raised. Wild-caught adults should be avoided due to their tenacious parasite loads and the short lifespan of wild specimens (quarterly or biannual breeders burn out faster). Finding clean specimens is well worth the wait, as Senegals raised in captivity can be as hardy as the toughest Ch. calyptratus and as tractable as the most mellow F. pardalis. The extra perks of keeping Senegals are small size, easy keepers, and "pet" bonding potential.

Physical Traits

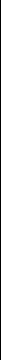

The Senegal appears to be Nature's base model in the Chamaeleo line. The dorsal crest is a single line of conicals that fade away towards the posterior, looking as though the decorating effort was abandoned. The single gular and ventral crest of saw-tooth conical scales is perpetually white in color, contrasting sharply with whatever body color it happens to be wearing.

The head is a cube and a pyramid compressed together, without a defined parietal crest, only supraorbital crests which sweep towards the occiput. These crests can achieve a range of colors from orange to self-colored as the body. The scales of some specimens' supraorbitals are asymmetrically and sharply keeled, like a row of tiny blades. Between the eyes, the head is concave, which collects droplets during watering sessions. Like the supraorbitals, the toes of this species can achieve a vivid orange color in contrast to the rest of the limbs. The distinct edge of the toe color looks as though they have been dipped in paint. Healthy Senegals of both sexes are a glowing leaf green in low light and a yellow-green (chartreuse) at roost. In captivity, they are exposed to our seasons. The shorter daylight hours of winter can induce a light brown coloration in both sexes, regardless of frequency of unfiltered sun basking.

Basking color is brown and may include the faint appearance of darker brown chevrons and spots along the body.This basking color can include white webbing (interstitial skin) over the entire pattern.

Content Senegals show the leaf green resting color overlaid with sky-blue chevrons or 'diamond' shapes, oriented vertically along the sides of the body, pale blue-to-white gular and inner limbs, and blue turrets.

An unusual calm color pattern contrasts the content blues merged with the cocoa brown basking color, including orange toes. Stress coloration is any of the base colors superimposed with fine black spotting. In extreme stress, they can achieve solid black (the soles and ventral crest alone remain unchanged). Some specimens have shown color morphs that affect the eye irises and the gular interstitial skin. Gold and red-orange irises are found among animals in the same shipment, as are gular interstitial skin colors of orange or purple. Red-orange eye irises are less common. One specimen was recorded to develop orange interstitial skin in a scar.

The squamation is homogenous, and a hydrated hide feels much like velvet. The texture compliments their no-frills form, as do their narrow, delicate limbs which resemble grass stems. The skin has photosensitive capabilities. A Senegal in good flesh has no evident muscle outlines on its limbs, no loose skin; it is fleshed smoothly, just as the rest of its features make a continuous form. Ribs are only evident when the body shows extreme postures, such as climbing or yawning. Adult males are easily determined by the symmetrical swelling of hemipenal bulges at the tailbase. The key to ideal Senegal body condition is "smooth", and any irregularities or bloat indicate a health concern.

Behavior

As graceful as the most horned, finned, lobed, or casqued chameleon, the streamlined Senegal makes up for its ordinary looks with its interesting nature. In my experience, Senegals exhibit some behavior traits that differ from most chameleons. These differences may be what make them better choices as a "pet" chameleon. Like mice, Senegals seek contact security in their environment. They thrive in densely planted enclosures. They will weave their bodies between branches and leaves, and only one corner of the enclosure must be clear for basking. They show the same preference for dense foliage, whether caged or free-ranged. Hand-raised Senegals may take contact security one step farther and behave as if their keeper is the foliage. They are the only species of chameleon this author has observed to repeatedly seek a partially-closed hand to perch inside, only exposed eyes rotating calmly, and remaining resting colors until removed from the "cave". To prevent readers from grabbing the first Senegal they see and wadding it up, bear in mind that the animal has to initiate this until it is familiar with the keeper. Another unusual trait: one can modify its behavior by artificial cues, even in the presence of natural stimulus. Simply put, you can train a Senegal to shoot when and which prey item you indicate, even in a free-roam environment with other prey in range. One hand is the perch, and the other hand points to indicate which item is next. Two identical, moving prey items may be within range, but the habituated specimen will eat the indicated item first. Yes, it has a tiny brain, but it does learn from repetition. It's hard to explain the expressions of visitors as you walk around your garden, commanding a small lizard with a casual finger-point. This ability to infer a location of a food reward from physical cues has been previously recorded in dogs1.While such induced prey choice behavior might be linked to general movement leading to increased attention to a particular prey choice, it at the very least shows how comfortable and trusting this species can be with it 's keeper. A third interesting behavior is a social cohesion observed only in juveniles and/or subadults. I was told about a trio of chameleons at a local herp shop that were spending all of their time perched in a line, holding each other's tails. When I went to observe this bizarre arrangement, I found two juvenile Senegals at the bottom of their enclosure, black with stress, frantically pawing the walls and showing searching behavior. I started looking around for a cause of the stress, and found a third tiny juvenile, also black, pawing and wandering around the bottom of a neighboring enclosure housing two adult Ch. gracilis. I alerted the staff to the problem, and when the stray was returned to the other enclosure, it scrambled right up and perched with the other two, as previously described to me, and all three quickly turned bright green. I had never observed such a display of sociability among chameleons at the time, and as it was unheard of in the species, I purchased them so I could continue observing and recording their behavior. The group dynamic continued to be strong for not days or weeks, but several months. They were kept on a free-range, so they could have separated and moved to other houseplants at any time.

The weights at purchase were 7, 8, and 9 grams; they were still juveniles. When one was picked up and given medication for parasites, the other two became agitated and even aggressive towards me, until I returned the animal to the tree. By day, they would bask together, often touching, and by night, they frequently assumed the line formation, holding each other's tails.

Senegal sexual maturity is approximately six months of age, and they were separated into cages as soon as the female grew aggressive towards the males (puberty onset). It is normal for adult females to defend their territory against males when they are not receptive. To keep the peace, it is recommended that all adults be housed separately. I collected one report of a LTC male that became aggressive to the keeper at the onset of puberty, and one report of a female that bit her handler during a veterinary procedure. In general, they are rarely aggressive towards keepers.

Senegals do share most of their behaviors with other chameleon species. A behavioral obstacle for many animals is stress over disruption of routine. Our interactions with chameleons are results of conditioned response, such that association with food and other comforts can bring. In theory, any person with food rewards in hand could elicit the same response from the animal. Chameleons can be touchy about this as they are visual animals and may respond to changes in keeper appearance. An extreme example of an inconsolable Senegal occurred when one was left in the care of a pet-sitter while the keeper went on vacation. A free-ranged single Senegal repeatedly climbed down from its range (this was a new behavior) and searched the home until dusk each day that the keeper was out of town. The pet-sitter was also house-sitting, and was able to observe this over the full course of the day, each day. The animal could not be coaxed to stay put with food rewards. It continually searched, staring at the sitter when he came upon him each time, then marching past. This behavior stopped abruptly when the keeper returned and the visual routine was re-established (feeding times and manner had not changed). Although nothing else about its environment had changed, this specimen had noticed that the wrong person was feeding it, and as a result, it was stressed. This searching behavior was not as dramatic as the previously mentioned juvenile separation display, since the chameleon did not turn solid black with stress. In such cases of stress, the conditioned animal will forego food rewards until the issue is corrected.

Captive Maintenance

Enclosure methods may be altered to suit the individual Senegal specimen. I have used free-ranges, PVC mesh tube cages, and aluminum mesh cages. Mesh of one-quarter to one-half inch is not recommended, as a Senegal can fit most of its rostrum through those sizes. It can develop stereotypy from the frustration of not being able to push all the way through. Standard window screen mesh is ideal for Senegals. I recommend a minimum cage size of 16 x 16 x 30" ( 40.6 x 40.6 x 76.2 cm) high for a single Senegal, and the larger the cage, the better. Fresh wild caught Senegals can be acclimated in a quiet room with a window free-range, then moved to screen enclosures a few weeks later without obvious stress. The free-range requires a live, densely foliated tree, a humidifier (out of reach), and basking UVB tube fluourescent and heat spots. Free-ranged Senegals thrive in a window; although the filtered UVB does them no physical benefit, it does provide psychological comfort. I have kept a LTC in a free-range away from a window, and he was fine with occasional hand-carried visits to a window for basking. During the summer months, it is highly recommended to house Senegals outdoors where their great joy, natural sunshine, can be experienced most hours of the day. To reiterate the importance of extremely dense plants for this species: Senegals will bask most of the day, but at temperature peaks, they may need to briefly retire to shaded perches. Dense plants also hold moisture longer, with lingering droplets for frequent drinks. With the exception of subadults as mentioned before, adults should be housed separately. Adult females are highly territorial, and will tolerate a male in the cage only for the duration of copulation. A free-ranged female will chase a male out of her tree all the way to the substrate. Senegals make the most of available water, and they thrive with automated misters. A drip system does not humidify the air the way a mist system does, and only hydrates a small portion of the enclosure in a vertical line. A mist system works best for Senegals because it permeates the enclosure air, it showers all over the animal's skin (when it chooses to perch in range), and gives more opportunities to groom the eyes. Check for feces often, and spot-clean where you find them. Senegals tend to drop waste anywhere, and only use a routine site in cold weather or in extreme old age (in other words, when they are not feeling like moving around). If you are diligent with spot-cleaning, you may put off tearing the whole cage apart for months. Keeping everything the same helps reduce stress to the chameleon. Senegals are content in ambient temperatures from 75°-98°F (24°-37°C) and humidity from 50-100%. Temperatures around 60°F (15.5°C) can cause lethargy and stress.

Diet

Senegals will eat almost anything that crawls into range. The complete lack of pickiness of the acclimated senegalensis makes them a welcome addition, an "easy keeper" in a collection of fussy species. Wild-caughts may choose to only eat cultured houseflies and small spiders for the first few weeks, but can be tempted by the finer things, such as silkworms and tiny hornworms. It's astonishing how much a Senegal can pack away in a sitting, and this leads to a health alert. It is very easy to over-feed this species, resulting in fatty liver disease and possibly bowel obstruction. On the positive side, Senegals respond well to the usual chameleon supplement dusts and proper cultured prey gutload formulas. If you have access to clean, wild prey, Senegals do not require manmade supplementation as long as they are housed outdoors and eating all wild prey. Senegals relish skippers, but please only feed butterflies, skippers, and moths if your local pollinator population is strong. This chameleon species will eat any suitably-sized prey item, so take care to keep stinging or venomous arthropods well away from their reach. A deparasitized pet Senegal, with all of its needs met, only requires 1-3 small to medium prey items per day, with one or two days of fasting a week. Animals that are in acclimation, growing, or breeding condition may require significantly more prey.

Health

There are several excellent articles that detail the parasites and diseases of wild-caughts, and if you wish to forge ahead with WC Senegals, read and expect everything, and share the documents with your vet when you have the WC examined. Hand-raised specimens, or past-quarantine WCs acquired as juveniles, are virtually the hardiest pet chameleon to be had. Healthy adult Senegals shed completely every three months, like clockwork, until extreme old age. The only maladies that I have seen reported in LTC specimens are dystocia and hemipene impaction. Sunshine, water, dense plants, and nutritious prey are enough to keep a Senegal in good shape for years longer than one would expect of such a small species. I had a WC male for almost five years to the day, and have collected anecdotal reports of WCs kept from two to over seven years. Expect 4-5 years from a captive-bred specimen kept properly hydrated and fed from hatching. The first signs of advanced age are a paling of the green body color and hollows above the turret inside the eye socket. Extreme old age is characterized by a thin look overall, minimal activity, and arthritic toe distortions. Older Senegal chameleons can benefit from softer prey to ease digestion and a soft "hammock" for basking to ease arthritic grips.

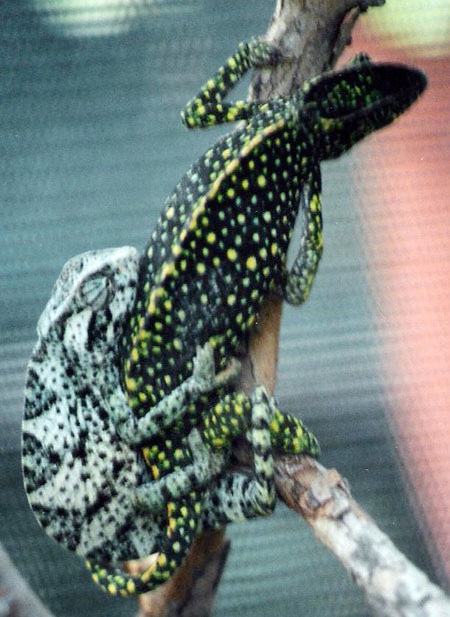

Breeding

Senegals can breed multiple times per year. I began testing a LTC female for optimal receptivity by showing the male to her. I tried her at random intervals. On dates prior to the breeding, the female responded aggressively at the sight of the male, even through heavy shade-cloth mesh. Unsuccessful test dates of August 11th, 16th, 18th, 25th, September 3rd, 9th, 15th, 20th, and 29th were followed by a breeding date of October 10th. The female showed increasing receptivity by staying out in the open, lower, and less-dense parts of her range, at first exhibiting a bright green with darker green chevrons, and three or four orange spots on each side. She changed position every five minutes, attracting attention with her movement and a color change to green with dark brown pattern. She began stretching her abdominals and cloaca as she perched. The male approached at speed, all the while dragging his cloaca and bulges along the branch. Even in his rush, he may have been leaving a pheromone trail to mark a temporary territory. Senegals at this stage of receptivity do not have a pre-mating ritual, copulation occurs immediately. I recorded a single copulation that lasted 2 hours and 46 minutes, during which the partners' color patterns changed. During the first 15 minutes of copulation, the male lashed his tail frequently and violently, which might serve to discourage any interloping males from approaching the pair.

At breeding, the female weighed 44 grams and the male weighed 18 grams. Both animals were calm when handled, which allowed me to track the gestation weights. Within the first 30 days, her breeding weight increased 18%, then 10% in 12 days, then 12% the next 10 days. Just before the two-month mark, her weight started to drop, warning of a problem. The known gestation can extend to 90 days, but on day 68, she dropped one egg on the substrate. The laying chamber contained a mix of sand, peat, and potting soil, friable but firm, and a top layer of dried leaves. I also put in a grapevine perch for her to rest on, which she did use frequently. She refused to dig, but continued to show contractions. At 72 days, the female succumbed to dystocia. Her color did not indicate illness or stress, as she maintained the "content" bright leaf green with orange toes color to the end. I advise other breeders to watch for behavioral and weight clues of dystocia with gravid senegalensis females. She had very obvious contractions, but could not pass more eggs. She had no history of illness nor MBD, and had been a healthy, eager eater. During gestation, she received a nearly 100% wild prey diet, dusted calcium supplements on the prey, and at the end, oral Neocalglucon drops. Just over 20 eggs were removed and incubated. This is considered a smaller clutch number for this species, in a range of 20 to 60 per clutch.

At one time, a web page detailed a British keeper's account of hatching this species. That page has since disappeared into the web void, but it offered an unusual approach to incubation. His female dug and laid a normal nest. He excavated the entire nest ball of eggs intact and incubated them en masse. He had success with this method, and at the time, it was more success than previously published. Before I found that site, I shared my clutch with a friend, thus the eggs were incubated under differing conditions to determine an ideal. We each incubated the eggs in the traditional method of individually placed in rows, in vermiculite, in plastic containers. At nearly two months of incubation, the eggs had noticeably enlarged. Egg size topped out at 5/8 inches (1.6 cm) long. Unfortunately, neither of us hatched any live senegalensis. My friend had them incubating at about 80°F (27°C) in moderate to low light, with gradual egg die-off. I incubated them in dark at 82°F (28°C), but the last week of incubation was a mid-summer cross-country move by car, driving only by night to keep temperatures safe for my chameleon collection. I kept the eggs in a soft-sided thermal food carrier with a thermometer. They experienced night drops of ten degrees F during this time, and the substrate was evaporating as fast as I could replace it. At some point in my travels, I suspect I miscalculated and over-moistened the vermiculite. At five months, the eggs were large and had fine stretch lines (much like those observed in R. brevicaudatus eggs). By six months, the outer white was peeling off at the stretch lines and large translucent patches were meeting across the shell surfaces. This can indicate the developing embryo's absorption of Calcium from the shell. At six months and seven days, the eggs showed surface droplets, then the eggs shrank and dented, but no pipping occurred. Three days after the eggs shrank, I opened them and found full-term, bright green neonates. It is interesting to note that LeBerre cited 3-4 months gestation for this species, but fertilized eggs and dystocia resulted at 2 months in a female kept isolated from the male since puberty. Keepers should stay alert for early clutches such as this one to avoid similar loss. Our temperature range was within those published in other sources, and the eggs did not have mold problems.

From my own experience of raising young senegalensis, and gathered experiences of other keepers, they can be very easy to keep. Young males of 9 grams in weight start to show hemipenal bulges. By about six months of age, the subadult can double its original size. By one year of age, the average adult female Senegal is six inches (15.2 cm) SVL. One LTC male was known to achieve that size by that age. The average male is about 20 cm total length, and my own LTC at this length topped out at 30 grams. The heaviest male I have heard of weighed 32 grams.

There is still much to learn from senegalensis. If you start working with the species, keep an open mind and open eyes: this plain little chameleon can be surprising.

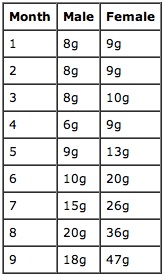

Juvenile WC Growth Chart

Additional photos:

References

Bartlett, Patricia and R.D. Chameleons: everything about selection, care, nutrition, diseases, breeding, and behavior. Hauppauge: Barron’s Educational Series, Inc., 1995.

Francis, Kristina. Unpublished journal records, 1/29/01- 1/26/06.

LeBerre, Francois, et al. The Chameleon Handbook. Hauppauge: Barron’s Educational Series, Inc., 2000.

Necas, Petr. Chameleons: Nature’s Hidden Jewels. 2nd ed. Frankfurt am Maim: Edition Chimaira, 2004.

Kristina Francis

Kristina began her journey with chameleons in 1999. She remains a perpetual student of this fascinating lizard family. When not busy caring for her chameleons, she is a professional animal artist. She is the editor of the Melleri Discovery web site, and a moderator of the mellerichams Yahoo! group. She breeds a clutch only once every few years, and shares her data on each species she works with. She volunteers each day to answer questions of fellow hobbyists, via phone and email. It all repays a small measure of the joy of chameleon keeping.

Join Our Facebook Page for Updates on New Issues:

© 2002-2014 Chameleonnews.com All rights reserved.

Reproduction in whole or part expressly forbidden without permission from the publisher. For permission, please contact the editor at editor@chameleonnews.com