Experiences with Furcifer lateralis lateralis

By Kevin Stanford

Citation:

Stanford, K. (2006). Experiences with Furcifer lateralis lateralis. Chameleons! Online E-Zine, May 2006. (http://www.chameleonnews.com/06MayStanford.html)

Morphology

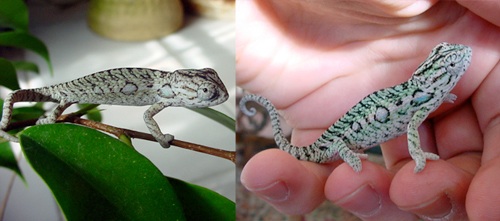

The smallest true chameleon species still legally exported from Madagascar, the carpet chameleon, Furcifer lateralis lateralis, averages 6-8 inches in length. Carpets are capable of intense displays of color and pattern, which can vary considerably between individuals. Generally, all possess ocelli of varying sizes that lie along a whitish lateral stripe gracing each side of their bodies (from head to tail-base). They possess homogeneous scalation. Males, which can easily be distinguished from females by their greatly enlarged hemipenal area, have a more subdued color palate than females. They generally exhibit mostly greens, yellows, blues, and white. Females often add to those colors soft pastels of pink, blues, and oranges. When gravid, females are capable of displaying gorgeous deep shades of bright red, orange, purple, blue, and yellow interspersed with striking black patterning.

Excited but not gravid Female (left) and Male (Right) Furcifer lateralis lateralis.

Not gravid Female (left) and Gravid Female (Right) Furcifer lateralis lateralis.

Necas acknowledges the major subspecies as a full species. Other authors do not. I would not recommend breeding the two types together, as they seem to be quite different in many aspects. Liddy Kammer reports different incubation methods working for major that would not work for her F. lateralis lateralis. I have bred a male major to a female lat lat that resulted in infertile eggs. This is not enough to convince me that they cannot interbreed, but it does sway my thinking in that direction. Regardless, I would not repeat this to see what happens anyway. It is very difficult to pinpoint just exactly what differentiates the two sub-species (species?). As I have heard it said, you know one when you see one. There are some differences I've learned to look for in my observations that I'll pass along. Male majors are noticeably bigger. They have a simple color and pattern scheme, free from all of the busy spots and such that lat lats commonly exhibit. Most male majors I've seen have a pinkish lateral stripe rather than white also, which is sometimes less delineated and more broad than in the nominate race, almost fading away at the edges into the background color. Female majors are less colorful, and also have less busy patterns with a good deal of pink along their sides. They don't adopt the same color-patterns when gravid either, instead taking on a blackish wash where the pink had been.

Female (left) and Male (Right) Furcifer lateralis major. Photos courtesy of Chris Anderson.

Habitat

Furcifer lateralis inhabits a large portion of Madagascar, excepting the North and Northwestern regions, and can be found at a variety of elevations, from sea-level to 2,000 meters above sea level. It is very adaptable and is not affected by human habitation the way that many other species are. It prefers humid forests, but can also be found in dryer areas, and around people (Necas 1999). Necas reports that they are commonly seen on fencing and bushes.

Trade Status

Carpets are listed on Appendix II of CITES, and are restricted to an export quota of 2,000 a year. There is no distinction made between the sub-species, and major is lumped in with the quota.

Acclimation

Wild-caught carpets are delicate and often carry internal parasites. They require a lot of hydration for the first month with regular showers and drippers combined with spraying. Fecals should be performed by a vet as soon as possible to see if treatment is necessary. The chameleons should be allowed to fully rehydrate, and acclimate to the new surroundings before being subjected to medications, in order to prevent further stress on the animals' bodies. Try to select juveniles or smaller adults when choosing from imported specimens, particularly in the case of females. Most of the time, wild-caught adult females are gravid, having bred before capture or during the holding process. I've had larger imported females acclimate successfully and lay eggs, only to have all of the eggs go full-term and die stillborn (because the babies were too weak to exit the eggs?). When compared to captive-bred babies incubated in a similar manner, there were distinct morphological differences. Upon opening the eggs, the wild-caught's still-born neonates were considerably smaller in size with dome-shaped heads. This happened with two consecutive clutches by the same female. This female was very large and appeared older when received as a fresh import. I can only speculate as to the causes, but much evidence exists to believe that the health and condition of the female greatly affects the resulting hatchlings (James Amirian-pers. Comm.). By targeting smaller females you can hope for a younger individual that has laid less clutches, still possessing positive reproductive capabilities.

With that said, captive-bred or healthy captive-hatched carpets should always be sought first. Just as in other species, it can mean a world of difference and sometimes be the factor between success and failure. Captive-bred animals should be free of any significant parasite loads, and adjusted to captive conditions, making them much more suitable for breeding projects. Captive-bred animals are uncommon currently, but an increasing number of people are beginning to have success with this species, so hopefully that trend will continue.

Captive-Care

Housing

Carpets are small chameleons, and are comfortable living in a habitat roughly half the size of what would be used to house an adult male panther or veiled. A cage with the dimensions 18" W X 16" D X 24" H will suffice. I keep each sex in the same sized cage since there is not a significant size difference between the sexes. I use all screened cages. Since an occasional individual will be a screen climber and rub its snout, I may decide to replace the sides of that animal's cage with fiberglass screening to prevent abrasions and injury. This is very rarely a problem in most cases, however. The cage should be thickly planted to allow these shy chameleons their privacy. This is especially important for new animals. Once they settle into their routines and become adult size, they usually stay out in the open and are easy to view nearly all the time. They are still shy when a hand enters their enclosure, however, and some will not hesitate to drop off of their branch, simply run, or hiss and even strike. Ficus and schefflera do well as cover for lat cages, and adding some branches both diagonally and horizontally will give the chameleon a place to bask, perch, and just feel comfortable. They must never be housed together outside of breeding attempts. No exceptions should be made regardless of the sexes one intends to house together-even females cannot be housed communally. Each of my cages is topped with one or two Reptisun 5.0 bulbs, and a 60 watt basking light. The basking light is simply a standard light bulb situated in a dome fixture. Carpets are avid baskers, and will not hesitate to take advantage of the warmth.

Hydration

My carpets will drink much more often that my veileds and panthers. They should have the opportunity to drink their fill every day. This can be accomplished through multiple hand mistings with warm water, and the addition of drippers. When using drippers they should be running for at least 4 hours during the day, and preferably longer. I have used gallon-sized drippers to achieve this. When hand misted, many carpets often begin drinking as the spray hits their faces, and will continue to do so for some time. Because this is time consuming when one has more than just a few animals, I installed automatic misters that go off four times a day for ten minutes at each session. For me, this has eliminated the need for extra hydration measures, allowing the chameleons to clean their eyes, drink, and "take in" the humidity.

Feeding

Crickets of ½" to 2/3" are the staple of my adult animals' diet during the colder months of the year. I will sometimes feed silkworms and stick insects (Medauroidea extradentata) as well. During the warmer months when insects can be collected from pesticide-free areas, I take advantage of whatever kind of grasshoppers come along, and collect moths on occasion. Since variety is at a minimum during the winter, I make sure that all of my crickets are well gut-loaded. I recommend using the Wells/James/Lopez recipe available on Adcham.com. I prefer to use crickets a little smaller than what is needed since larger-sized crickets are reported to retain less of the nutrients gained from gut-loading than are smaller crickets (Ferguson 2004).

Carpets have very healthy appetites, with females seeming almost gluttonous at times. Controlling the amount of food a female consumes is important, to keep her from producing eggs too often and in too great of numbers. I don't have a set schedule to supplement my animals with calcium or vitamins. On average, I usually dust the crickets with Herptivite and Calcium from Rep-Cal about twice a month. Once every one-to-two months I rotate by using Reptivite by Zoomed, instead of the aforementioned. That is to add some pure form vitamin A into their diet, albeit very sparingly.

Outdoor Housing

Living in the northeastern section of the United States brings its limitations in regards to outdoor maintenance of chameleons. Still, I manage to be able to keep my juvenile and adult animals outdoors 24/7 starting at the end of May-early June, until the first week of September. I experience the fewest health problems during this time of year, and truly feel comfortable with this situation. I very rarely supplement animals kept outdoors during the summer…maybe three times during the entire span on average. Carpets can take a wide-range of temperatures outdoors, and mine have stayed outdoors during daytime highs around 95F, and nighttime lows dipping to 40F. Both of those temperatures are at extreme ends of the spectrum though, and I feel most comfortable in the 50F+ night/70-85F day range. They should be in a position that receives sun through a good part of the day, but be provided with adequate shade should they need to seek refuge from the heat as well. Thickly planted cages are important. I will only put them outside with automatic misters, and set mine to go off for 15 minute sessions, six times a day. This is just what I do, and may need to be adjusted depending on whether or not your climate is warmer. This is only meant to be a very general guideline. With outdoor maintenance, it is much easier in my experience to care for them. It is nice to let nature do some of the work during the warmer months.

Breeding and Reproduction:

Despite showing up on dealers lists every year as wild-collected specimens, captive-bred, and even captive-hatched Furcifer lateralis lateralis are only available on a very sporadic basis, and cannot be found reliably. There are many reasons for this. Wild-caught specimens very often fail to acclimate and do not live long enough to reproduce in captivity. Imported gravid females often lay unhealthy clutches of eggs, with many infertile eggs. Many females fail to dig a nest and scatter their eggs around the cage, dropping them from a branch. This may end up with the keeper finding the eggs later, after they have desiccated beyond recovery. In addition, many "lat" keepers find that the eggs do not always respond to standard incubation techniques used for similar species, such as panther chameleons. To add to this confusion, others do have success with these techniques. Some suspect that this latter phenomenon may be a result of the geographical location that the parent animals were obtained from, meaning that different climatic conditions on the island of Madagascar lead to different incubations for the same species. Perhaps it is a combination of these circumstances that prohibits the commonality of captive-bred stable populations of lats in the hobby up to this point. I will provide information about what has worked for me, and what hasn't, in hopes that others will build off of this and continue to improve the captive-husbandry and propagation techniques of this beautiful chameleon species.

Breeding Age and Size

Females can reach sexual maturity as early as four months old. I have even read of younger females producing eggs but have not seen this with my own animals. A female's first receptive cycle can be recognized by the beautiful coloration they begin to take on, which up until this point has generally been a solid green background with some darker patterning. Instead, they adopt a pastel theme, with a light yellow wash providing the canvas. Add to this a distinct orange bust of color running the length of the chameleon's side, with light blue filling in the ocelli. The dorsal line takes on a blue and black alternating pattern, with bits of red sometimes creeping in. This is a generality, since the wonderful thing about carpets is the variety between individuals regarding their colors and patterns. When they reach maturity though, you should notice the change in color quite easily. The earliest I've bred any female is 5 months of age, with a snout-to-vent length of 2.5 inches. I have also held off until 8 months of age for breeding. Like so many other breeders have recommended for practically any species of chameleon, I too feel it is definitely safer to wait until the female is older to begin breeding. Eight months has proven safe for me, and they can be raised to this age without laying infertile clutches. I've experienced more difficulty keeping females from laying successive clutches of eggs when breeding at a young age. Carpets are experts at retaining sperm and developing more clutches, whether bred again or not. About two weeks after laying, a female will become receptive, and if not bred within a couple weeks of that point, will usually become gravid again regardless of what the keeper wishes. This can be controlled by restricted feeding and keeping the supplements to a minimum, but for me it has proven much more difficult with this species than veileds and panthers.

Receptive 5 month old female F. l. lateralis

Courtship

Courtship consists of the typical head-bobbing and jerking movements on the part of the male. Some males are eager and will rush towards any female placed in their cage, while others are more subdued and shy, preferring to feel the situation out first. An unreceptive female can be very aggressive, gaping at and chasing the male while adopting vivid black patterning. If the female is receptive, she will show little sign of aggression, sometimes walking away slowly and relaxing her color. Actual mating usually lasts around 20-25 minutes.

Laying and Clutch Size

Females are reported to lay as few as 4 eggs and as many as 23 (Necas 1999). Clutch sizes for me have ranged from 11 to 19 eggs. Healthy adult females usually lay around 15 eggs per clutch. Gestation almost always lasts about 30 days. Females can be fairly particular about their nesting sites, and frequently drop their eggs from the branches of their cage instead of digging a nest. This is due to the keeper's failure to provide a site that is found suitable by the female. It is suggested that females are prone to digging nests when the substrate temperature is kept warm. I have not seen enough of a correlation between substrate temperature and nest digging to make firm conclusions. Rather, certain females seem much more inclined to dig nests than others for me. I generally use a mix of potting soil and sand. Drier substrate seems to be favored, and placing the female in a laying receptacle outside of the cage can help also. I have on one occasion, had a female that dug a nest in a receptacle that was kept inside the cage. To play it safe, a layer of moist sand or something similar can be added to the bottom of the cage about a week before the female is expected to lay. This way the eggs will hopefully stay hydrated until the keeper finds them, should the female decide to drop her eggs instead of digging a nest. One trick to getting the female to lay in a nest can be to pre-dig one for her. I have, on three occasions, actually pre-dug about half of a tunnel for a lat, only to have it finish the tunnel on its own and use it for egg-laying. Any nests that were dug by my females never exceeded 4 or 5 inches in depth, despite being given a foot or more of substrate to dig in. This goes along with the published literature on this species. I have heard from other breeders that their lats will dig nests quite a bit deeper. Again, I wonder if this is a geographically linked trait, in response to that area's climate.

Wild female excavating a nesting site. Photo courtesy of Eric Anderson

Incubation

I have used vermiculite and more recently perlite to incubate lat eggs, moistened at a level that would be used to incubate panther eggs. I prefer the perlite, for now, and appreciate its tendency to give the eggs adequate breathing room between the substrate and the eggs. Carpet eggs typically undergo a diapause in the wild to adapt to seasonal changes. Diapause is the early embryonic developmental arrest of eggs laid in the warm, wet season, in order to survive the following cool, dry season while dormant, and/or to allow neonates to develop and hatch in the favorable warmer climate the next year/season. There are those breeders who do not simulate diapause, a cooling period of typically 1-2 months, for carpet eggs. One of the most successful lateralis breeders I have spoken with does not use the diapause method. Again, this may be because their lats were imported from an area in Madagascar with more stable temperatures year round, or perhaps other reasons. I don't have the answer for this. I have seen many aspiring carpet breeders become frustrated and give up because much of the time the eggs fail to develop, despite being in incubation for extended periods of time. Sometimes not using the diapause method will work fine for one clutch, while the clutch next to it fails to develop at all. The first carpet eggs I ever came across, laid by a wild-caught female, incubated 8 months without a single blood vessel developing inside. Later, these eggs slowly shriveled without ever having vascularized. Using conditions that roughly emulate Madagascar's climatic seasonal changes in my incubation methods, including a period of diapause, I have achieved predictable results time and again. I keep the eggs at room temperature (68-74F) for roughly 45 days after being laid. Next, the eggs are placed in a mini-fridge set on the lowest setting, with the door left open a crack. The goal is to keep the eggs in an environment where the temperatures hold steady between 50-60F. After 45 days of this, the eggs can again be kept at room temperature for the rest of incubation, with eggs vascularizing 2 to 4 weeks after being removed from cooler temperatures. Babies will generally pip, after the egg has sweat and shrunk, about 120 days after breaking diapause. Length of incubation can vary depending on temperature. Keeping the eggs warmer (77-79F) can make them hatch earlier, as reported by other breeders. I prefer to keep mine at 68-74F. Adding water to the substrate can spur hatching in full-term eggs. It can also lead mishaps. I've seen quite a few instances of breeders apparently drowning babies or causing premature hatching because of adding water, and recommend allowing the babies to hatch when they are ready (James Amirian, Susan James, Pers. Comm.).

Neonate pipping out of egg.

Since this method has proven so predictable, it would only seem logical that eggs may go through a similar cycle in the wild. Since nests average 4 inches in depth, they may be more likely to experience temperature fluctuations that nests a foot down in the ground would not be exposed to. As mentioned earlier, perhaps in some areas lats dig deeper nests, and therefore this may be why the eggs sometimes respond well without diapause. This is, of course, just speculation.

Hatching on vermiculite.

Care of Hatchlings

Though small, the young are not difficult to care for. They adapt readily to individual housing in small cages. I currently use 7" cubed baby cages, with one to three babies per cage. Babies should be housed individually if space allows, because this species is fiercely territorial. I've seen day old hatchlings opening their mouths and displaying at each other. More aggressive hatchlings may intimidate shyer clutch-mates, leading to stress and decreased food consumption. The cages are filled with plenty of fake plants for spray water to accumulate on, and topped with Reptisun 5.0's, and a 40 watt basking light from day two on. Babies are initially fed on fruit flies, both melanogaster and hydei, supplemented two to three times a week with vitamin and calcium supplementation. I usually introduce baby crickets gutloaded on the Adcham recipe into their diet, within a couple weeks of hatching. Babies can be sexed right out of the egg. After viewing a number of baby lateralis, it actually becomes quite easy to sex them by looking closely at the tail base for the hint of hemipenal development that will become very obvious in males within the next two months. Babies grow very fast, and are nearly adult size by five months of age!

One month old male (left) and three month old male (right).

Five month old female with hatchling on her back.

Closing

Thus far I've bred F. lateralis lateralis through two generations. I am raising my F2's now in hopes of carrying the species as far as I can. This has been a rundown of my experiences with this, my most favorite chameleon species. As I go along I'm sure I'll continue to fine-tune my husbandry and breeding techniques. I encourage others to use this information as a springboard to further our husbandry knowledge and understanding of this species in captivity, so we can ensure multiple-generation captive-bred animals are available for hobbyists to enjoy.

Special Thanks

I would like to thank James Amirian for sharing his knowledge with this species, and being patient enough to help me get my start with them. I'd also like to thank Susan James, Liddy Kammer, and Carl Cattau for helping me along the way, in trying to decode some of the mysteries this species can present to its keepers.

Sources Cited:

Necas, Petr. (1999). Chameleons: Nature's Hidden Jewels. Malabar, FL. Krieger.

Ferguson, G., Murpy, J., & Ramanamanjato, J. Baptiste (2004). The Panther Chameleon. Malabar, FL. Krieger.

Kevin Stanford

Kevin grew up in Northeastern Pennsylvania, keeping and breeding various species of native and exotic herpetofauna before moving onto chameleons about 5 years ago. His current focus is on carpet chameleons, though he also keeps some panthers and veileds, along with poison dart frogs. An avid field herper, Kevin has done work with the Fish and Boat Commission assessing local rattlesnake populations. Currently he is in his last semester as Penn State University, graduating with a BS in Business Administration.

Join Our Facebook Page for Updates on New Issues:

© 2002-2014 Chameleonnews.com All rights reserved.

Reproduction in whole or part expressly forbidden without permission from the publisher. For permission, please contact the editor at editor@chameleonnews.com