Hornworms!

By B. J. Caruthers

Citation:

Caruthers, B.J. (2005). Hornworms!. Chameleons! Online E-Zine, December 2005. (http://www.chameleonnews.com/05DecCaruthers.html)

READY TO FEED GREEN MONSTERS TO YOUR GREEN MONSTER??

or

Is your sweet little rainbow-colored scaly friend ready to dine on cute little green cat(erpillar)s?

Blaze, having a snack

There are some excellent online sources which offer very comprehensive information on rearing hornworms. One in particular, The Manduca Project, is a great reference for building rearing and feeding cages, photos, videos, educational tools, life cycle, school lesson plans and more! I know some of you are not interested in the taxonomy or other, more scientific, issues but would rather a quick guide to answer your current burning questions and not to read through a lot of text to find them. So, rather than reinvent the wheel, I thought the best use for you is to write out some basics and background but have also set up a Q&A format. This way, you can quickly look up what you need, or read the entire article.

If you are a vegetable gardener, you are probably all too familiar with the tobacco (Manduca sexta) and/or tomato (M. quinquemaculata) hornworms. These are the large green caterpillars, which can reach 4” in length and attain a body diameter of ½” or more! They are extremely well hidden among your tomato plants and once you find one you may wonder how the heck you missed it! Place it back on that stem or under that leaf and - it has gone! Even their reddish, in the case of M. sexta, or black, M. quinquemaculata, horn seem to blend right in. These intimidating creatures are harmless, but the bane of many gardeners and crop growers. They are not worms at all, but the larval stage (caterpillar) of two closely related species of Sphinx moth.

Hornworms are great feeder insects for you chameleon - just not freshly plucked from the garden. They feed on not only tomato and tobacco plants, but all in the Solanaceae family, which also include: potato, peppers, eggplant, deadly nightshade, petunia, nicotiana, Datura (aka thorn apple or jimson weed). The foliage and stems of all of these plants are TOXIC TO SECONDARY FEEDERS - YOUR CHAMELEON! The Manduca species (spp.) have developed both mechanical and physiological ways to protect themselves from the toxins, much like monarch butterfly larva and its toxic host plant, milkweed (have to cover that another time). You may have seen some of their cousins flitting around your garden on warm summer days such as the “hummingbird” moth Hemaris thysbe or the white-lined sphinx, Hyles lineata.

Hemaris thysbe - Image Courtesy of Seth Ausubel

Hyles lineata - Image Courtesy of Faith in Arkansas With permission from Bill Oehlke

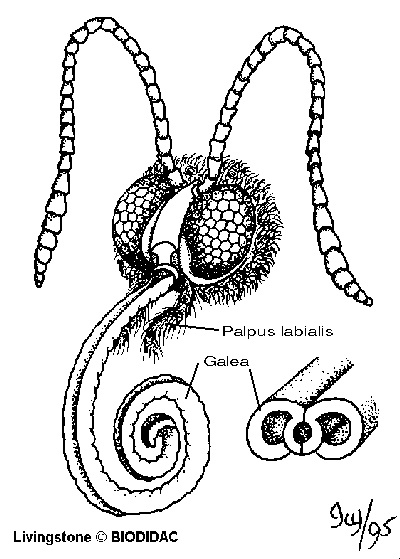

But you will not see the adult moths of the veggie garden type flitting around unless you look for them at night. These adult moths are important pollinators and are found throughout the U.S. Because their proboscis (tongue) is 2-3x their body length, which is 2-3”, they have to hover while nectaring at flowers much like a hummingbird does.

Manduca quinquemaculata - Feeding on Datura drawn by Paul Mirocha

There are many other hornworm species even some, like the Abbott’s (below) without a horn and just a spot where it once was!) in the sphinx family, but we will only cover the two that are readily available to the chameleon keeper and, for our purposes, I will refer to both the tobacco and tomato hornworm simply as hornworm and the adult moth as Sphinx, which brings us to...

Sphecodina abbottii - Image courtesy of Sherleen Smithson

A BIT ABOUT NAMES

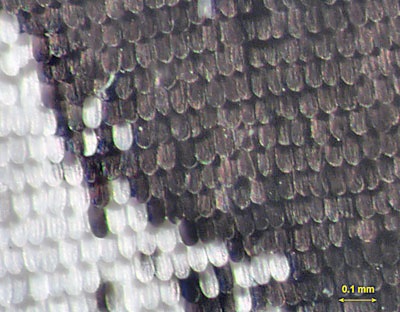

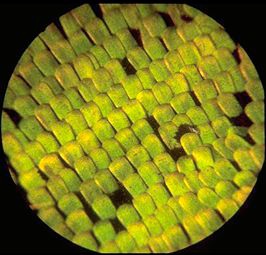

All moths and butterflies are of the taxonomic order Lepidoptera. The word comes from the Greek lepidos = scale and -ptera = wing. If you were to look at a moth or butterfly wing under a microscope you would see that it is covered with overlapping scales. These are actually modified hairs covering a transparent wing and what appears as the soft powdery-like substance that covers their wings and comes off if handled. Obviously, not scaly as we herpers think of scales, but they are in fact scales. They actually look like this:

Wing of Cabbage White Butterfly - Images courtesy of Graham Matthews

Moth Wing - Images courtesy of Graham Matthews

Manduca sexta (Man-doo’-ka) comes from the Latin: Manduca = glutton (no clarification needed here!) and sexta = six-fold, which refers to the six abdominal stripes on the adult moth.

Manduca sexta - Image courtesy of John Himmelman Connecticut, July 1999

Manduca sexta larva - Image courtesy of Dan Janzen

Whereas the Manduca quinquemaculata (kwink-kew-mak-u-lay’-ta) quinque = five and -maculata = spotted explaining the five abdominal spots or stripes on this adult moth.

Manduca quinquemaculata - Image courtesy of Tim Dyson. Peterborough, Ontario

Manduca quinquemaculata larva - Image courtesy Extension Entomology Texas A&M University

The family name is Sphingidae and have a couple of common names you might recognize: Sphinx moth, which refers to the way the caterpillar holds its body when disturbed, during a molt, or at rest. Another is hawk moth and is attributed to their quick and effortless flight. These are extremely strong fliers and have been known to travel great distances for a mate.

A QUICK LESSON IN TERMINOLOGY and BIOLOGY

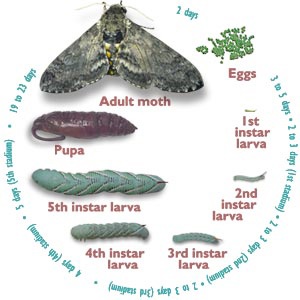

The larva, or caterpillar, is the stage between egg and pupa and will shed (molt) its skin four times (the period between each molt is called an instar) and then one final time as the new skin below is hardened, thus forming the pupa. Some moths, like the hornworms, have naked pupa and are earth, or subterranean, pupators. Others form a cocoon of silk surrounding the pupa and the butterflies create the chrysalis a firm, protective membrane. Regardless of the form, they are all for protection from predators, camouflage into surroundings, or to burrow below a frost line. The duration of this stage varies greatly and is dependent on a number of environmental and physiological factors such as temperature and day length - see DIAPAUSE. (Note: larva/pupa = singular; larvae/pupae = plural)

The pupal stage is the period of final metamorphosis into the adult (imago) moth or butterfly. Without going into the specific physiological process, very simply put, the larva, as we knew it, more or less liquefies and all the parts are restructured, thus forming wings, antennae, etc. Lepidoptera larvae have three pair of “true” legs near the head, which they use for holding and maneuvering their food, guiding silk from their spinnerets (located in lower mouthpart - labium) and are the only ones remaining in the adult moth or butterfly. The other “legs” in the middle (four pair) and rear end (one pair) are called prolegs and are used to cling to a branch while feeding, resting, or molting and “disappear” in the adult stage. The prolegs of many caterpillars, including hornworms are extremely strong. They have little hooks, called crochets, which results in a strong grip and adhere much like Velcro. Never pull or force a hornworm from a branch if holding tight as you can tear its integument (skin) or actually rip off a leg :(. The time spent in the pupal phase can be as short as a few weeks to over 10 months.

Understanding the basic biology of your hornworms will help you in breeding them. If you are just keeping them short term in order to feed off and then ordering more from a breeder, you do not have to know this - but the information is here for those with a curious mind.

In brief, an insect does not have a “brain,” at least not in the sense of thinking as we and other mammals do - they are more or less mechanical creatures. When we see them move, fly, sting, feed, etc., it is all in response to light, temperature, threat and other environmental factors. Like a salmon swimming upstream to spawn, insects just do what nature has “programmed” them to do. Insects have a hormone called the juvenile hormone (JH), which is responsible for triggering each molt. As the JH decreases with time, the insect is then closer to its adult stage. Insects do have circulatory, reproductive, digestive and central nervous system - not unlike other organisms - regardless of how many feet they may have!

All insects take in oxygen through spiracles, which are small openings along each side of the thorax and abdomen. In caterpillars, these are often obvious as you can see here to the lower left of each diagonal marking.

Manduca sexta larva - Image courtesy of Dan Janzen

If you dust a hornworm and your cham does not eat it, I suggest putting it in a separate container with food and expect that it may die. Premature mortality may ensue because the fine dust can obstruct the airflow.

FEEDING AND BREEDING

AN IMPORTANT NOTE

DO NOT COLLECT HORNWORMS FROM YOUR GARDEN AND FEED TO ANY ANIMAL

There is a readily available artificial diet for hornworms (similar to silkworm chow) that must be used for feeding to avoid poisoning your chameleon.

What do I need to keep and feed hornworms?

Q. Where can I get hornworms?

A. There are a number of online sources to purchase hornworms that have been reared on an artificial diet, therefore safe to feed to your cham; see Resources.

Q. Where can I get the chow?

A. Any place that sells the hornworms as feeders also sells the chow. If you plan only to feed them off and not breed them, you can order them in cups with (usually) enough pre-made chow to last until you are ready to feed them off. It is a good idea to have extra powdered chow on hand in case you run out.

Q. How do I make the chow?

A. Whomever you get your chow from will certainly include instructions, but I am giving them here so that they are even more readily available and/or you can print them out. These instructions are provided by Mulberry Farms.

COOKING INSTRUCTIONS (For Powdered Hornworm & Silkworm Chow)

MICROWAVE OVEN (preferred method)

CAUTION: Use at least a 1 1/2 quart microwave safe container at least 5 inches deep for each 1/2 lb. packet of Chow or it may boil-over.

-

1.Add 1/2 lb. of powdered Chow to 24 ounces (3 cups) of hot tap water and mix thoroughly by hand until all traces of powder are gone. (A wide butter knife works well for mixing.)

-

2.Place a sheet of plastic cling wrap over the top of the container to retain moisture.

-

3.Cook on high for several minutes until mixture begins to boil (it will puff up and rise to about one-third higher than its original level).

-

4.Turn off microwave and stir for a few seconds for uniform consistency.

-

5.Repeat step number 3 (for about 2 minutes), and then step 4 again.

-

6.Immediately place a sheet of plastic wrap inside the container and press it against the chows surface so it clings directly to the surface of the hot chow. This will prevent excessive condensation from forming and help keep the chow sterile.

-

7.Allow cooling, then putting lid on, and placing into refrigerator.

-

8.Remove from fridge, peel back plastic wrap, slice and serve when firm. After the Chow cools, it should have a consistency similar to soft cheese.

WARNING: Do not handle the cooked Chow unless your hands have been thoroughly washed. Hornworms are very sensitive and susceptible to bacterial problems if their food is not kept sterile.

NOTE: The cooked Chow will keep for a month or more in the refrigerator if kept airtight. The powder can be stored for about 6 months if kept in a cool dark place, or longer in a refrigerator (WE RECOMMEND REFRIGERATING)

Each 1/2 lb. of powder makes approx. 2 lbs. of cooked Chow, enough to feed/grow approx. 500 silkworm eggs into 1 1/2 to 2 inch long worms.

Tips & Pics:

-

•Follow the directions and you should have no problems

-

•Be Careful! The steam released after opening the cling wrap is very hot! (212+ degrees F can leave a painful burn)

-

•I suggest using glass rather than plastic as there are still questions as to which chemicals can leach from plastic to food

-

•Wash hands before, during and after preparing!

-

•Use CLEAN utensils. If contamination happens, you will be throwing out a whole batch of chow - and maybe your larvae, too! Using disposable plastic gloves (often sold for painting projects) can certainly minimize the chance of contamination.

-

•I cut my chow into smaller chunks and wrap individually so that if there IS any accidental contamination I only lose a small amount.

(photos below are of silkworm diet. Manduca diet only varies in color)

Silkworm Chow - Powder

Silkworm ChowCooked and sliced

Chow - cut, ready for feeding or storage

Q. Can’t I just make my own artificial chow mix?

A. Yes, you can. There are a few different recipes, however, you may need some ingredients not readily available to you. There are two recipes online and they vary slightly. The Purdue Entomology Dept. Hornworm Recipe gives all the ingredients and amount needed and The Manduca Project Diet gives you the list, but no specific quantities or preparation. Unless you plan to do this on a commercial basis, your easiest approach is buying the powdered chow to have on hand and make as needed.

I did find a recipe for a homemade diet on UWisc-Madison Department of Entomology’s website (see Resources). I have not tried it so cannot comment on it from experience. If you try it I would be interested in your success and experience!

Q. Why can’t I feed them plants from my vegetable garden?

A. Hornworm caterpillars feed on not only tomato and tobacco plants but all plants in the Solanaceae family, which includes: tomato, tobacco, potato, peppers, eggplant, deadly nightshade, petunia, nicotiana, Datura (aka thorn apple or jimson weed). The foliage and stems of all of these plants are toxic to secondary feeders - your chameleon.

Q. How much do they eat?

A. A lot! They are eating machines and only break to shed their skin, which takes a couple days each time. So make sure you have plenty of chow available if you plan to be feeding them for very long.

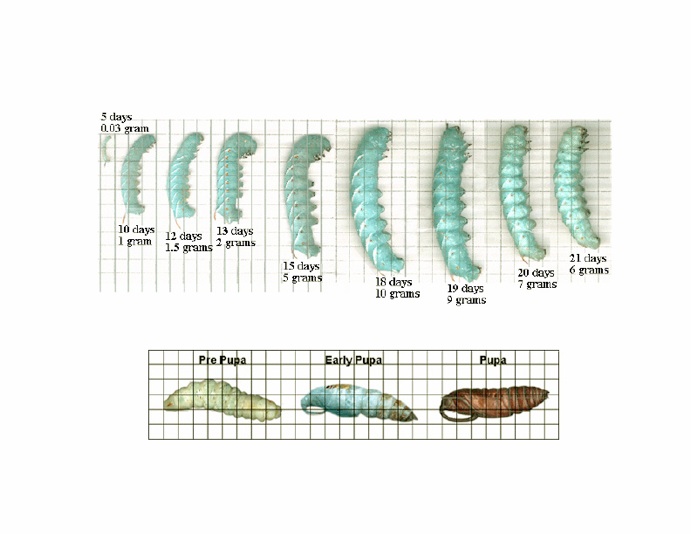

Q. How fast do they grow?

A. Typically, egg to final instar is about three weeks. Here is a life cycle chart to give you an idea

Q. Can I slow them down - or speed them up?

A. Yes, you can regulate this to some degree by temperature. Warmer - quicker, Cooler - slower. Do not expose them to temps under 50 degrees; do not put them in the fridge. You will be feeding these off over time so feeding the largest first assures you have an ongoing supply.

Q. How do I feed them to my chameleon?

A. You can hand feed, place on branch, screen or cup feed, Their Velcro-like prolegs allows you to “stick” them just abut anywhere - but be prepared for the food to wander looking for food itself!

Q. At what size can I feed them?

A. The rule of thumb for feeding is that the insect is no longer than the width of your chameleon’s head but, like silkworms, these are soft bodied so you can stretch that rule a bit.

Q. How nutritious are they?

A. They are very high in protein (approximately 58%) but also high in fat, therefore, you would not want to feed a steady diet of these to your chameleon. You should always offer a variety of food.

Q. I have read that they bite. Can they hurt my cham - or me?

A. Other than biting each other (if reared in too crowded container and/or not enough food) the mandibles (chewing mouthparts) are not strong enough to cut through human or lizard skin. They do have a habit of thrashing their heads and sometimes “spitting” at perceived predator. The “spit” is regurgitated food and is a defense mechanism - as is the head thrashing - when disturbed and sometimes when handled. Neither of these will hurt, but may startle you. If your chameleon grabs a hornworm by its head, it may grasp onto the chameleon with its prolegs. Do not force the hornworm away, if the cham has not been able to dislodge it you can gently “peel” the legs from the chameleon, but the clamping of the hornworm’s head by your cham’s jaws will more likely cause the hornworm to thrash than to grasp. On the other hand, like Blaze, your cham may just get enough of a grip where neither of these will be a problem!

Its horn, which is a firm yet pliable protuberance, cannot cause any problem either. It too, is used in nature to deter any would-be predators (primarily birds).

Q. What is happening when it is just sitting still for a long time with its head reared?

A. They are either resting or molting. See more info on molting in BREEDING section below.

Q. I have seen pictures of hornworms with white things sticking out of its back - what are these?

A. Hornworms are frequently parasitized by a species of Braconid wasp, Cotesia congregata. A female wasp deposits her eggs inside the soft body of her “host.” The wasp larvae feed on the caterpillar’s insides and then pop through the skin and spin small white cocoons - this is what you see. The caterpillar is doomed. There has been speculation about whether there is a natural anesthetization taking place in order for the hornworm to feed as it normally would. If it stopped eating the wasp larvae might die as well. Some of us like to think this insect “Novocain” is a fact, as we cannot imagine what the poor fellow feels. Remember, they DO have a central nervous system and therefore can feel pain.

Manduca sexta covered in Braconid wasp cocoons - Image Courtesy of Matthew Roth

Braconid wasp, Cotesia congregata - Courtesy R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company

In captive rearing there is less chance of this, but it is a small wasp and can slip through loose or wide screening and other cracks. If one of yours does become parasitized you can let it go so that the wasps live (they keep the Manduca population in check) or you can feed it to your cham, as the wasps will not hurt it. Although it is a parasitic wasp, it is not a parasite of lizards or other 4-legged creatures. Your cham will just get a bit more protein!

If you plan on buying your hornworms from a breeder, raising them and feeding them off, you can stop reading here. For those of you who want to actually breed and maintain an ongoing supply you need to realize that the lifecycle timing is quite different from other Lepidoptera you may have raised such as: silkworms, monarchs, swallowtail, polyphemus moth, but if you want to give it a go...read on

BREEDING

As I mentioned earlier there is copious information online for rearing with, in my opinion, the most comprehensive being The Manduca Project and I recommend you check it out. The wealth of information that is available via this site is truly found nowhere else - all under one cyber roof, that is. It was created mainly for rearing in the classroom by The University of Arizona, but since it is freely available online, we can all benefit. Due to the size attained by the hornworm, they are used extensively to teach students about metamorphosis. For this same reason, they are used in laboratory research; if you are interested in learning more about that aspect see the links at the end of the article. Note: I suggest reading this section in its entirety beforehand as you will need to do a little advanced planning (see section on Diapause)

Q. What do I need to breed hornworms?

A. Other than checking out the suggested resources, here are some things for you to know about hornworms and how different their needs are from other Lepidoptera you may have raised. Many of you have likely raised silkworms and figure hornworms cannot be much different - well believe me, they are! One fact about silkworms, due to their centuries-long history of “cultivation” for the silk industry, is that they are now rendered flightless. They are cousins of the wild silk moths, which do not feed as adult moths, however, the sphinx moth not only needs to feed, but needs to hover over its plant due to its long proboscis. This can be a difficult feat in confinement unless you have a large enough setup. See below for detailed info on feeding moths.

Another important difference is the natural length of life stages. In northern climates, the pupal stage can last up to 10 months. In warmer climates it is around 3 weeks. The time can be anywhere between these two depending on environmental cues such as soil, length of photoperiod (day length).

LARVAE

There are several ways to rear your larva, but the basic plastic storage box container is fine for non-commercial breeders. The Manduca Project has an excellent article on setting up a rearing box. Similar to the silkworm set up using plastic canvas as a ventilated bottom for frass elimination, this one uses ¼” hardware cloth. The hornworms get much larger than silkworms and, as would be expected, so does their waste! Be sure to dump the frass regularly and not allow it to get too humid where mold will develop.

Images courtesy The Manduca Project

PUPAE

Q. How do I know when they are ready to pupate?

A. There are several cues to let us know when they are getting ready. The first is the heart line, which runs along the center of the back. When nearing pupation you can see it pulsing through the stretched, translucent skin.

Most larva wander while looking for a place to pupate. This is done for any number of reasons, but in the case of the hornworms, it is due, in part, to them being subterranean, or earth pupators. In nature, they obviously need to leave the plant in search of appropriate soil conditions for burrowing. I have reared a number of Leps and the hornworms are serious wanderers, maybe second to the cecropia. Believe me, you will know! Another key is change in their appearance. In the growth chart below you can see that the larva actually begins to shrink; it “clears its gut” in order to rid itself of any excess fluid before its long rest. You can see the beginning of this change in the chart below.

Stages of pupal development - Images courtesy of Tim Dyson With permission from Bill Oehlke

As they get smaller, they need to shed their final skin and should not be disturbed. Even though these creatures have been doing this for millennia it is always a delicate process and one which can prove fatal if not respected. By this time, you should have it in its pupation chamber.

There are a few ways to do this:

The Soda Bottle Method

If you plan to bring only a few through pupation, you might want to try the method that Purdue University’s Entomology Dept. has created. It is a fun way to experience the pupation (especially if you have children!). I used this method to rear my very first Sphinx moths and it was successful and educational! You can watch it wander then burrow and because of the soil displacement due to soda can the hornworm will be visible through the plastic. You will see the actual shrinking and changes as it moves from the larval stage to the pupal. The setup is HERE.

Deep Soil Chamber

In the wild, they burrow 10-18” below the soil line, so a 5-gallon bucket is nice but not necessary. Fill with barely moist peat leaving a few inches of space from top, set the hornworm on soil, cover (it will wander out if left uncovered - I have more than once had “cats” wandering around the house!) and let it go. I would not recommend more than ½ dozen per this size container; adjust accordingly.

No Burrow Chamber

You can also place them into an appropriate size container, place several crumpled up paper towels and empty toilet paper tubes on their sides in with the caterpillars. Cover. They will wander and eventually settle below the towels and pupate. The cardboard tubes mimic the chamber they create in the soil. This method is used often by breeders and researchers of many earth pupators due to the simplicity.

DIAPAUSE

Diapause is a quiescent period where any growth is in arrested development. No need for food or other sustenance, much like hibernation in some mammals or brumation in some reptiles. In Lepidoptera, this is usually, but not always, the pupal stage as is the case of the Sphinx moths (some go through diapause in the egg or even the adult stage such as the mourning cloak butterfly). The length of time is determined by environmental factors, either natural or induced, primarily during the larval stage. Sometimes exposing the pupa to cold temperatures for a short time and then to warm temps is sufficient to “break” diapause, but it can also be regulated by day length (photoperiod) in the larval stage.

Q. How long before they emerge as moths?

A. If you live in the north and want to follow nature, be forewarned that your moth may not appear until summer. I had one that pupated in August and eclosed the following July! But if so, you would remove your pupae from their chamber, lay them on barely moistened peat (sterile, never before used) cover and put in vegetable crisper section of your refrigerator. You can also leave them outside in a rodent/bird proof container. Covering with ¼” hardware cloth works fine. Here is a homemade mating cage, which can also be used as a wintering over cage (with its top in place). This can remain in a cold area such as garage, barn or outside to be exposed to natural temperature and moisture variations. Keep out of direct mid-day sun

However, in order to have the moth continue to develop and not enter diapause, this way eclosing (emerging) 4 weeks after pupating, you will need to expose the larva to 13-15 hours of daylight, mimicking early season photoperiod (day length). This can be done with UVB light setups if normal day needs to be extended.

ECLOSION

If the pupae are in soil they will wiggle their way to the top, (just imagine that hard, brown case moving through the soil to reach the above ground world! Amazing!) split their pupal skin and work their way out. They come out all crumpled and folded so it is IMPERATIVE THAT YOU PROVIDE SOMETHING FOR THE MOTH TO CLIMB ONTO IN ORDER TO UNFURL ITS WINGS. These will then “harden” (sclerotize) and be ready for flight. This will be a 6-8 hour process, so once again, do not disturb. You can use a stick in the soil or propped up in the bucket you have your pupa in JUST BE SURE that this is in place and secure long before they emerge. You cannot wait until the last minute and hope you get it there on time. Alternatives are a piece of screening, fabric or even tape paper towels to the sides and they will easily climb these surfaces. They will not crawl far before needing to climb so make it easy. Remember, they have a 3-4” wingspan so the eclosing cage needs to be of sufficient size.

When the adults emerge, they secrete a fluid that will come squirting out. It is water soluble, so no worry if it gets on anything. See a video of both wing inflation and the eclosion process

The Tale of Toby: My first Manduca rearing experience (1999) resulted with one of the seven crippled. I had everything in place. After a day of classes I came home to find that one of the sticks had dislodged and what I saw was a moth, on its back, all twisted and crippled - yet very much alive. I was devastated. I hand fed Toby twice a day for several days (that is when I learned the proboscis unfurling with a pin technique). It was grueling. I finally placed him in the fridge and then the freezer. To this day, he resides on a bed of dried lavender flowers in my living room. Whenever I do a Wild Silk Moth presentation, I bring him along to tell his story in order to emphasize the importance of “the stick!” These are not very clear photos (7 years old) but you will get an idea of Toby’s plight and how I had to prop him far enough away from the nectar source - and see his long proboscis.

Toby feeding, proboscis fully extended

Proboscis partially extended

And here he is today. You can clearly see the “handle” on the pupal skin, which housed the long feeding tube.

Q. What sort of setup would I need for adult feeding and mating?

A. FEEDING - This is where things can get tricky. As already pointed out the moth needs to hover, or at least be able to perch just the right distance, over its nectar source. Being chameleon keepers, you may very well have large enough screen cages or even an outdoor setup that you could relinquish to the moths. If so, you would keep fresh, tubular flowers/plant in the cage for free-flying feeding and/or also attach some sugar water (approx. 10% -20%) solution. Be sure to boil water and then pour over measured sugar. Stir with clean utensil to dissolve, let cool before offering) soaked in plain tissue (no perfumes, dyes, etc.) and placed in dishes or in a homemade feeder (see rearing box link). If you are not fortunate enough to have a screen cage setup, you can create your own with the directions on Rearing Box page of The Manduca Project. This setup can be used for nearly the entire life cycle.

You can also try to gently hold the moth by it wings at the thorax and uncoil its proboscis with a dull pin or toothpick. This is NOT for everyone. I did this with a crippled adult moth for several days and it is not easy. The coiled feeding tube is in close proximity to the eye and you could very easily miss as the moth struggles. I think you will be surprised at the strength this insect has in its flight muscles! Or as mentioned earlier, you can try to touch the antennae with a bit of the SW solution. I personally was not successful in this latter method.

Drawing of the coiled feeding tube. It lays closer to the eyes, resting between the palpi, which is why this can be a dangerous operation - and is probably not needed.

MATING

The moths’ eclose in late afternoon and around dusk of the first evening they are ready to find a mate. Not much you have to do here other than having males and females together! After mating, the female will begin to lay eggs on the underside of leaves. You can place the mated female in a large brown paper bag and she will lay. Collect what you need and then release her so she can deposit the remainder. You can cut out the pieces of bag with the eggs and places them in your hatching. The disadvantage of using the bag is that she will bang up her wings badly while seeking places to deposit. In nature, she would place them on many plants. If laid all in one area there is more chance of predation which would minimize the overall survival rate - and they have enough problems with those Braconid wasps! Some moths are rather passive and the bag method is OK, but with a sphinx, you will end up with a very battered moth. Keep in mind, they can lay 200 - 700 eggs(!) so think ahead of how many you really want - remember, the larvae are heavy feeders!

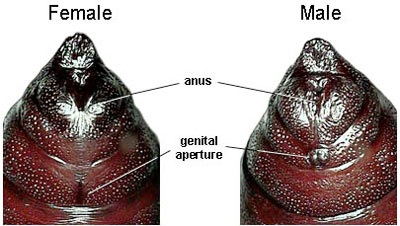

Q. How do I tell a male from a female?

A. Unlike some other moth families, these are not easily sexed by their antennae, which are very similar. You can tell if you have a good eye. In a sectional view, a female’s would appear round, where the male has a ridge at bottom. It is easiest to determine in the pupal stage.

Images courtesy The Manduca Project

Images courtesy The Manduca Project

Q. What do I do with the eggs?

A. The eggs will hatch within 3-5 days. Have their food source ready and you are on your way! When first hatched they are quite pale and their horn is very long. Once they begin eating, the color will get darker and they will “grow” into their horn. Watch the videos of laying and hatching

NOTE: due to their short hatch time you will likely not find eggs for sale.

CONCLUSION

In a (rather large) nutshell, you have all you need to know in order to successfully feed and/or breed hornworms for your scaly friend. Just keep in mind that if you go thru the entire life cycle you might just find yourself naming one or two yourself - they are handsome moths.

One interesting note, I have never and likely will not feed a hornworm to any of my herps. The Manduca sexta from our veggie garden was the experience that eventually brought me to breeding the Saturniids (Wild Silk Moths) which has become a passion and a source of my - and others’ - enrichment. So, in memory of Toby, my herps remain hornworm-free ;)

Manduca quinquemaculata - Image courtesy of Norma J. Wood from North Central Texas

RESOURCES

Larvae & Chow

U.S.A.

Mulberry Farms

SilkysToGo

herpfood.com

Canada

Rearing

UW-Madison Department of Entomology

The Manduca Project

Chow Recipes

Purdue Entomology Dept. Hornworm Recipe (pdf)

The Manduca Project Diet

UW-Madison Diet

Photos and Videos

BugGuide.net

The Manduca Project Videos

Research and Science

Jan Dolzer's Manduca Home (Jan was the one who helped me care for Toby)

Detection of Sex Pheromones

Manduca sexta Research Links

Teachers Resources

The Purdue Department of Entomology’s Educational Outreach

Lesson Plans

The Sphinx Moth

B. J. Caruthers (lele)

Known as lele to fellow herpers, B. J. Caruthers lives in NH with her veiled chameleon, Luna, 2 cats, 2 tarantulas, and many 6 -legged and 4-winged critters. She has degrees in Horticulture and Nature Literacy & Expression and enjoys writing, drawing and photographing her wild silk moths and other jewels found nature.

Join Our Facebook Page for Updates on New Issues:

© 2002-2014 Chameleonnews.com All rights reserved.

Reproduction in whole or part expressly forbidden without permission from the publisher. For permission, please contact the editor at editor@chameleonnews.com