Experiences in Raising Baby Chameleons

By Franco Gagliardi

Citation:

Gagliardi, F. (2004). Experiences in Raising Baby Chameleons. Chameleons! Online E-Zine, November 2004. (http://www.chameleonnews.com/04NovGagliardi.html)

Introduction:

Several housing techniques for the rearing of neonatal and juvenile chameleons are currently practiced. Such techniques include, but are not limited to, the use of small screen cages, milk jug habitats, aquarium set-ups, and sweater box enclosures. Each of these methods has undoubtedly resulted in countless stories of success, and perhaps, even some cases of disappointment. Like many, the author has tried several different styles of enclosures to house his hatchlings and juveniles. With much trial and some unfortunate error, he has settled on a technique that has resulted in the maturation of dozens of strong, healthy Furcifer pardalis babies and an extremely low mortality rate. In this article, the chosen housing method of the author will be described as one option available to chameleon keepers.

When housing baby chameleons, like any aged chameleon, one must ensure that they receive optimal lighting, proper hydration, thermoregulation, nutrition, and peace of mind. The dilemma of optimization leads one to consider a number of possibilities. Screen or glass? Real or artificial plants? Misting or Dripping? Fluorescent lights or natural light? Single or group housing? The list goes on and on.

An individual housing technique utilizing Kritter Keeper enclosures is the author’s housing method of choice. Success with group housing has been recorded, but after switching to individual housing, the mortality rate has nearly vanished. While there are hundreds of variables when dealing with hatchlings, the author feels this change has created a benefit without any noticeable consequence to the chameleons. Space requirements and the added expense of providing additional enclosures are the two main drawbacks of this technique; however, the chameleons seem very uninterested in the additional space and cost burdens. In light of space restrictions and the extra cost, the results have been well worth the effort.

Note: The author has only used this method with Panther Chameleons (F. pardalis). Whether is would work equally well with other species has yet to be determined.

The Method:

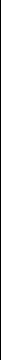

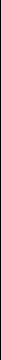

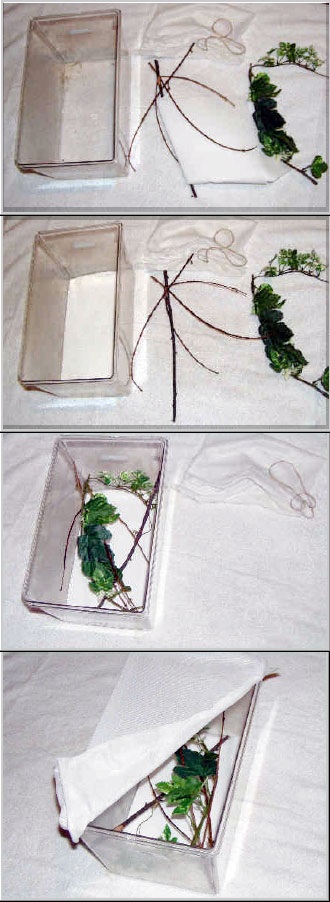

Shortly after hatching, the neonates are taken from the incubation chamber and placed individually into a fully furnished, small Kritter Keeper. The furniture is comprised of a trimmed paper towel, several perching branches, and foliage. The container is then topped with a fine mesh cloth, secured with a large rubber band. The paper towel is trimmed with scissors, or folded so that it lays flat on the bottom of the container. Several layers, created by folding the towel, are preferred for added absorption. However, excessive folds allow for extra hiding places for pinhead crickets. Two to three layers seem to work well without providing too safe a haven for the prey items. The branches used are cleaned and trimmed so that no string-like pieces (that can be chewed off and choked on, or swallowed resulting in a possible impaction) of bark remain. Dried grapevines and/or mulberry branches are the author’s perch of choice, but any clean and sturdy branch would work equally well. The branches are placed at several heights within the enclosure to allow the baby to get where it feels comfortable. Both natural and artificial foliage have been, and are currently being used. Depending on the time of year, one type is usually used with much more prevalence than the other. During the spring and summer months, and even early fall, grape leaves or mulberry leaves are used. During the winter months, artificial plants are used. The foliage provides the opportunity for the hatchlings to hide, find shade, and for water droplets to form during misting. The top of the enclosure is made from a fine mesh cloth obtained from any store that sells fabric (e.g. Wal-Mart). Different colors of a suitable cloth are available, but white is the author’s preferred color because it does not affect the natural coloring of the inhabitants. The material should be cut so that it covers the top with a few inches of overhang on all sides. If the material is cut too short, it will eventually shrink to the point where it is either very hard to secure, or completely useless. A top that is slightly compromised by too small of dimensions will allow for the possibility of escape. After the chameleon is safely in its new home, a name label is created and put on the container. The enclosure is then placed in a row of 7(the amount the fits comfortably on a 4 ft rack), with a 4ft Zoomed 5.0 fluorescent light placed directly on top. When feeding or misting, one corner of the mesh top and rubber band are unfastened and the necessary tasks are accomplished.

After reading the above description, many questions may be pondered as to the author’s reasoning.

Why use a small Kritter Keeper instead of a screen cage to house the individuals?

A solid-sided enclosure was decided upon because it keeps the tiny food items contained. Fruit flies, pinhead crickets, and most obviously, leafhoppers and other wild captured prey items are very capable and prone to escaping through the openings in the metal or synthetic screen used in cages. The leafhoppers and other captured bugs are drawn to the light and will seek to get as close to it as possible. Thus, in a screen cage it would be virtually impossible to contain them, as they can easily fit through the holes and get to their bright destination.

In regard to the size of the Kritter Keeper, small was chosen as the most appropriate for hatchlings. The small volume of the container allows for less terrain to cover when hunting. After a month or two of growth, the babies are upgraded into the medium-sized Kritter Keeper. As they out grow the medium-sized Keepers and their food becomes too large to escape through the openings in screen, they are moved into small screen cages.

How can he catch enough bugs to feed to multiple clutches of baby chameleons?

Note: The author always makes sure that the insects caught for chameleon consumption are from a pesticide free area. Before dispensing the bugs into the enclosures, he examines the contents to make sure that none of them pose a choking threat or could potentially harm the babies.

Living in Northern California, the author is fortunate to have the opportunity to capture a large majority of the food needed to satiate his brood. With a few slight modifications, a mosquito net, two metal clothing hangers, and some thread were transformed into a device that has been responsible for the ingestion of hundreds of thousands of leafhoppers (Exitianus exitiosus) and other bugs of an appropriate size. The babies seem to have an overwhelming preference for leafhoppers and eat dozens per sitting. From late April until early September, neighborhood lawns and the municipal bodies of grass provide ample hunting ground. When hunting for the leafhoppers, several considerations must be made. Temperature, moisture, angle of the Sun/availability of shade, quality of grass, day of the week, and wind are all significant factors.

Temperature:

Temperatures between 75-95º Fahrenheit seem to be optimal, although the mid to upper end of that spectrum tends to be better.

Moisture:

While the grass needs to be maintained, the presence of water makes capturing the insects very difficult. Not only do the bugs seem to be much more scarce immediately after rain, watering, or even morning dew, if they are present, water on the net will easily kill your captives.

Angle of Sun/Shade:

The angle of the sun plays an important role when trying to isolate the fruitful areas of the grass. Unless you are especially lucky, lawns and fields will not have an equal distribution of insects. Some areas are much more prolific than others, and when the sun is lower in the sky, the hopping or low flying bugs are much easier to see.

Shade, be it from a tree, a house, a fence, or the crown of a hill, also contributes to success. During the hotter days, the shade allows the bugs to escape the sweltering heat and blinding sunlight. Also, the grass that experiences shade at some point in the day tends to be less likely to excessively dry out. The contrast between bright and shade makes the hoppers stand out and more susceptible to capture.

Quality of Grass:

Healthy vibrant grass is much more likely to possess the leafhoppers than overly dry, sparsely placed, weed-infested grass.

Day of the Week:

While the day of the week seems to stand out of the list as peculiar, it must not be overlooked. It is not that the insects have a preference for one day over another, but if you are searching public property, the lawnmowers certainly have a set schedule. Freshly cut grass is one of the most damaging things that can happen to a successful hunt. There are few days more frustrating to an avid leafhopper hunter than freshly cut grass. Not only do clippings clog one’s net and make distribution a nightmare, but also, the local population of the hoppers seems to be at the lower end of their abundance cycle.

Wind:

Last, but certainly not least is, the presence of wind. Wind affects both the bugs’ flight and one’s netting ability. The stronger the wind the harder is it to isolate the prime areas of grass. Also, the technique of circling with the net, locked in catching position is not feasible because when changing directions, the net is either blown shut, or the bugs are blown out of it.

Once a suitable body of grass is found, the bug catching is commenced. Traversing the field in an expanding spiral is the most efficient use of one’s effort. As you walk, you should notice the leafhoppers and other bugs jumping every time you take a step. Therefore, by placing the net near your feet (adjusting its angle as needed) and walking, the bugs pretty much catch themselves. With the net held in the outer hand, you can be sure that the net is doing more work than your legs will be. The radius of the circle created from the center point (origin) of the spiral to the net, will be greater than the radius between the same center point and your legs. Therefore, the circumference of the circle traced out by the net will be larger than the distance you end up walking. Additionally, the speed at which the net moves will be faster than the speed at which you will be walking. The higher net speed is created because both your body, and the net are turning around the circle at the same angular rate, but being that the net has to move farther in the same amount of time, it ends up moving faster. The increased speed of the net helps to capture more bugs in less time.

During the winter or after a spring rain how does he feed his babies?

During the winter, and at all other times through the year, a back-up supply of fruit flies, pinhead crickets, and/or pinhead silkworms are on hand. All three can be self-sustaining if proper precautions are taken.

How does he water the baby chameleons when using the Kritter Keeper set-up?

The hydration of neonates is another very important aspect of their husbandry. When using the Kritter Keeper set-up, it is very important to make sure water does not puddle and stagnate in the enclosures. The need for the enclosure to dry out between mistings is extremely important, otherwise bacteria and fungus can (and will) develop.

Another consideration is that tiny bugs drown easily, and puddles are virtual magnets for pinhead crickets.

Misting two to three times per day (with warm water) allows the container adequate time to dry. Depending on the ambient room temperature, the misting schedule should be adjusted. However, extreme temperatures should not be reached or other problems are likely to result. When misting, care should be taken to avoid spraying the neonate directly. The reactions vary from one chameleon to the next, but to be on the safe side, it should be avoided. The more calm babies hardly react at all, while the more animated ones will gape, hiss, jump, and in some cases, will turn and bite themselves. The bizarre actions seem to be an instinctive reaction to having an unwanted presence of contact on their bodies. Also, there is always a risk of inhalation of the water and subsequent drowning.

Dripping is not recommended (from a dripper or ice cubes) because the nature of a solid-sided container is to contain, thus, flooding is inevitable. Furthermore, the nearly freezing temperatures of melting ice do not seem to be appreciated by a 2-inch long cold-blooded creature.

Why aren’t heat lamps included in the description?

Heat lamps are not included in the description because they are generally not used. The temperature in the room where the babies are kept is monitored and kept within an acceptable range (between 65-90F). The lower end is only reached at night, and it rarely gets that low. The higher end is only reached during the warmest part of the summer and is not for an extended period of time. The proximity of the fluorescent lights (placed directly on top of the containers) provides some heat, but the ambient room temperature is the main control and it stays between 75-85°F. In the case that additional heat is required, low watt incandescent bulbs can be added using clamped fixtures.

Does he ever expose the neonates to direct sunlight?

Yes, when the weather is permissive, the groups of individual containers are brought outside in cycles. The length of exposure is dependent on time constraints and on temperature. EXTREME caution is always, and MUST always be taken when bringing babies outside (especially when in solid-walled enclosures). Overheating and death can result in a matter of minutes. The author is extremely mindful of this fact and will not leave any container in direct sunlight without constant supervision. A misting session is provided before bringing the groups out into the warm sunshine, and usually, the containers are placed in the filtered light of a tree. The tree reduces the intensity of the light without compromising its beneficial qualities.

While direct sunlight is always beneficial, the author has raised hatchlings through the winter without bringing them outside. As long as proper nutrition and adequate artificial lighting (e.g. Reptisun 5.0 UVB) is provided, success is possible.

There was no mention of supplementation!?

When feeding the neonates leafhoppers and the other wild bugs, no supplementation is provided. It is presumed that the wild caught insects are full of a wide variety of nutrients. This presumption has been backed up with anecdotal evidence of dozens of babies growing into healthy juveniles.

Growth of male Sambava Panther Chameleon

Growth of male Nosy Be Panther Chameleon

Growth of female Sambava Panther Chameleon

When feeding the babies fruit flies and pinhead crickets, a calcium supplement is added every two-three days. The crickets are gut-loaded with a variety of nutritious things. The author is a strong believer in the James/Wells/Lopez gut-load recipe that is available through the AdCham web-site (www.adcham.com).

Clutch of baby Sambavas

How often does he clean the containers?

The containers are cleaned whenever they need it. To be less vague, a cleaning every week has proved to be effective. A cleaning encompasses changing the paper towel and cleansing the inside of the container. Rinsing with water and a mild cleanser is suitable. If one is using natural plant clippings, the withered leaves will also need to be changed during the cleaning. If using artificial plant, the synthetic leaves will need to be rinsed and inspected.

How secure are the tops of these containers?

The tops are as secure as the keeper maintains them. Rubber bands have a tendency to degrade over time, especially when exposed to heat and moisture. Thus, they should be checked weekly to make sure their integrity has not become jeopardized. At the first sign of weakness, they should be replaced.

The material size is an important factor and hangover is a necessity. The hangover allows for secure contact between the rubber band and the cloth.

What damage can a tiny chameleon do to a cage-mate?

Well, for a tiny creature, a baby chameleon can inflict serious and potentially permanent damage to a cage-mate. A squabble between siblings can result in tail-nips, scars, blindness, stress, and even fatal wounds. Of course, with large enough enclosures, adequate climbing branches, and careful supervision all of these serious injuries can mostly be avoided. Unfortunately, it is virtually impossible to watch the babies constantly, and even well behaved babies can surprise you. If one were to become startled, serious injury can result. Hypothetically speaking, let’s say that after “lights out” one of the babies decides to go for a midnight stroll. During his walk he happens to climb onto something that is a little softer than the ordinary branch. This soft branch with a curly tail lurches forward and hisses. The sudden movement of the “branch” startles the midnight stroller and he loses his balance. As he falls, his quick reflexes allow him to grab onto a nearby “curly branch”. His strong grip and the weight of his body bend the “curly branch”. In the morning everything seems normal, except one of the babies has a permanently twisted tail.

As a precautionary measure, the babies are housed individually. Not only does solitary housing ensure the absence of physical violence, but it also reduces the possibility of psychological torment from a dominant cage-mate. When housed individually, all babies have an equal opportunity to hunt and perch as they see fit. The author places visual barriers between the cages so that even the most timid hatchling receives the comfort that he or she deserves.

What makes this technique better than others?

As previously mentioned, many techniques are used and many work well. There is not one technique that is necessarily better than another; any technique that results in a low mortality rate with the all of the babies maturing into healthy adults is a good technique. The hope of the author is for this article to be seen as one of many alternatives.

The goal of all breeders and keepers should be to provide the best conditions for their chameleons to grow and develop. To ensure that one is providing the best care possible, one should obtain as much information as they can and never, ever, settle for mediocrity.

Franco Gagliardi

Franco Gagliardi has worked extensively with chameleons for the past 8 years. During that time, he has had the pleasure of hatching countless baby chameleons. When he is not tending to his breeding group, he can be found walking purposefully through any large body of grass catching bugs to feed to his hatchlings. If you happen to see him, please feel free to say hello. At the end of the day, once all of the chameleons have gone to sleep, he spends his time apprehending loose crickets with the help of his trusty canine sidekick, Bella. Franco has a B.S. degree in Mechanical Engineering from UC Davis and was an Assistant Editor of the Chameleons! E-Zine from May 2004-February 2007. He can be e-mailed at calumma.parsonii@gmail.com.

Join Our Facebook Page for Updates on New Issues:

© 2002-2014 Chameleonnews.com All rights reserved.

Reproduction in whole or part expressly forbidden without permission from the publisher. For permission, please contact the editor at editor@chameleonnews.com