Chameleons and Habitat Destruction

By Christopher V. Anderson

Citation:

Anderson, C.V. (2003). Chameleons and Habitat Destruction. Chameleons! Online E-Zine, May 2003. (http://www.chameleonnews.com/03MayAndersonHabitat.html)

Those who are interested in chameleons generally want to see their long term survival in the wild. There are many factors currently putting this survival in jeopardy. Most recently a trend toward conservation of chameleons has been centered on the elimination of the legal pet trade and the collection of wild specimens for it. This is, however, only a short term solution. For effective management and conservation to be effective in the long term, the natural habitats of chameleons must be further protected. Current efforts are not enough for many species. The only way to fully ensure the survival of chameleons in the future is to approach the factors impeding their survival from all sides with special concentration on those most vital aspects, specifically the protection and maintenance of their natural habitat.

Deforestation and habitat destruction are problems which we are taught about at school from a very young age. These issues are often shown in publications and on television with horrifying photographs of logging, slash and burn agriculture, erosion and other gruesome images. The dangers of habitat destruction are particularly abundant in third world countries which constitute the majority of the nations inhabited by chameleons. Agriculture is a large part of the economy and therefore, the land has a value that is too high to be ignored by the government, as well as families struggling to survive in these nations. This value creates incentive for the locals to harness the land and use it for profit. The areas of particular concern are those which are not protected by park systems and whose destruction could easily lead to the extinction of species with highly specified habitats. In order to prevent these needless extinctions, measures must be taken to protect their habitats from needless destruction.

The efforts that have gone toward hiding the destruction in the past and present are quite disconcerting and the minimal efforts made to conserve habitat are in some cases laughable. In 1977, the Arabuko-Sokoke forest on the northern coast of Kenya was declared a forest reserve.1 During that same year, one could drive into the forest, park on the side of the highway and immediately enter what appeared to be natural forest. From the highway it was not noticeable that the forest had been heavily logged approximately 40 yards from the roadside. The strip along the roadside that was left intact, according to one researcher working in the area at the time, was to disguise the lumbering.2 Not until 1991 was any of this area protected under National Park status and even then only an inconsequential 6km2 out of the total 358 km2 was set aside. At the time 54% of the locals continued to support the complete elimination of the forest for agricultural use.1 Protection of this 1.7% of forest with its fauna, including chameleons, and most importantly its endemic species of birds and other animals is a small gesture designed to pacify those who advocate its preservation.

Currently, large portions of original chameleon habitats have been destroyed and a very small portion of the remaining pieces are protected by parks. According to Brady and Griffith3 in their report on Malagasy chameleons, in 1985 only 34% of Madagascar's original forest remained intact. Andreone4 reports that in Madagascar, only 6% of the forest is protected and that there is extensive fragmentation of the remaining forest which chameleons inhabit. Jenkins et. al.5 states more recently that 5-6% of Madagascar's tropical forests are in protected areas. Within East Africa, Spawls et. al.6 notes that there are a number of vulnerable areas that are not currently protected and that there are many large areas that have never been surveyed and thus one cannot assess their relative importance in terms of conservation. The unprotected portions of the Usambara Mountains in Tanzania are home to many endemic species. Extensive logging for tea plantations in these mountains could potentially have disastrous effects to the local endemic chameleon species.7

An example of the importance of habitat protection is Bradypodion excubitor, a chameleon species only found on the eastern side of Mt. Kenya. In Kenya, exportation of chameleons for the pet trade has been banned yet illegal collection and exportation persists. This example of the effects on a wild population of chameleons after export has been banned is highly valuable to analyze. The highly limited range of this species of chameleon is being heavily logged and due to the fact that this species does not occur in any protected areas, the future of this species is in question.6 Since there is no legal collection dwindling the population and habitat loss is still damaging the species, it is clear that habitat conservation must be a high priority in the protection of this and other species. Numerous other species are at risk due to habitat destruction under similar circumstances. Chamaeleo (Trioceros) laterispinis from Tanzania for example has yet to be exploited for the pet trade to any significant extent yet Spawls et. al.6 state that this species is "vulnerable (possibly endangered) owing to habitat destruction." The numerous species at high risk for this reason are in varying states of threat. The sooner these areas can be further protected, the better the chance of saving these threatened species becomes.

One must be careful to look at each species individually with regard to their normal distribution and status. While some species are adaptive to habitat alteration, many are not and the result has shown to be the extinction of many species. Species that inhabit specific micro-habitats and thus are very restricted in habitat selection are most prone to the disastrous effects of habitat loss. A vital note however is that these disastrous effects for one species could bring about an increase in the population of another species. It is therefore important to take into consideration the natural state of the habitat prior to human interference and the original balance between the multitudes of species. This is often difficult to accurately assess due to the prolonged effect humans have had on the habitat of some species.

In their study of chameleons in southern Nigeria, Akani et. al.8 were able to carry out their work in three areas although one area is of particular note. In this habitat, deemed "Area A", they were able to conduct their study prior to and after the lumbering of approximately 40% of the site. In 1998, prior to the lumbering, a 45 hour survey of the chameleons in the area yielded a total of eight chameleons: 4 Ch. (T.) oweni, 1 Ch. (T.) cristatus, 1 Ch. (Ch.) gracilis and 2 Rhampholeon spectrum. In 2001, after the lumbering had occurred, another 45 hour survey yielded 7 chameleons: 7 Ch. (Ch.) gracilis. The probable local extinction of three species or at the very least, drastic decrease in the number of these three species present in "Area A" resulting from the lumbering of the site is a strong example of the fragility of some species to habitat alteration. The fact that the numbers of Ch. (Ch.) gracilis increased so greatly shows that this species actually benefited. It can be noted that the density of the local chameleon population as a whole did not differ significantly but the diversity of species declined drastically. They concluded in their study that "these findings support the hypothesis that the population of free-ranging chameleons declines in rainforest habitats where rapid changes in the environment are occurring."8 This conclusion shows that, despite the increase in the concentration of once species, the overall population diversity is adversely affected.

Jenkins et. al.5 conducted a relative study in Madagascar on the effects of forest disturbance and river proximity to the abundance of chameleons in Madagascar. In their study, they surveyed chameleon populations in a riparian zone, high disturbance forests and low disturbance forests for comparison. Their study included six species known to inhabit each area: Calumma brevicornis, C. gastrotaenia, C. globifer, C. nasuta, Brookesia minima and B. thieli. Each species was shown to have a higher abundance index within the riparian zone than either the high or low disturbance areas although the difference between the riparian zone and low disturbance area in C. brevicornis was marginal. B. minima was the only species which was not observed at all in high disturbance areas and every species, with the exception of C. globifer, had higher abundances in low disturbance areas than in high disturbance areas. They concluded that, despite the higher abundance of C. globifer in the high disturbance area, disturbance of natural habitat was not beneficial for the long term maintenance of chameleons. Additionally they pointed out the need for recognition of the importance in preserving riparian habitats for species conservation.

It is interesting to contrast these results and observations with that of Hódar et. al.9 in studying habitat selection of Ch. (Ch.) chamaeleon in southern Spain. They found that chameleons were recorded in developed zones while they were not found in nearby natural environments. Due to this finding, they have recommended that, for the conservation of this species, the populations require maintaining what they called "traditional human land uses" in conjunction with methods to lower casualties from roads and increase protection of nesting grounds. Ch. (Ch.) chamaeleon appears to be an example of a species that, at least to a point, seems to survive with the presence of a certain amount of development.

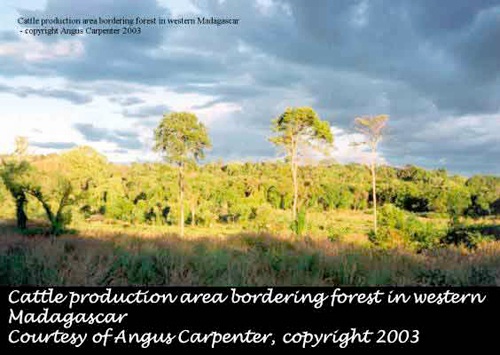

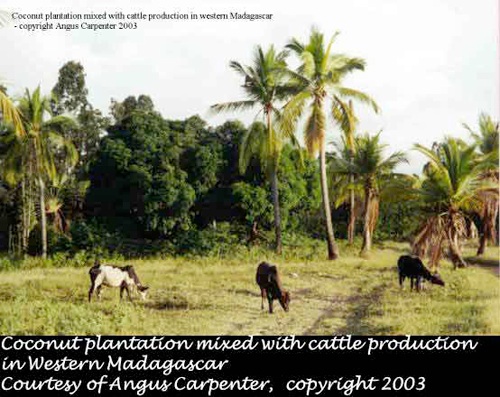

Deforestation and habitat destruction creates a number of other problems to chameleon habitat. A common problem with deforestation and logging is erosion. Madagascar is often called the bleeding island as during the wet season, the red soil being swept into the ocean by the rivers can be seen for great distances and gives the appearance of the island bleeding to death. While arboreal chameleons are not immediately affected by sheet erosion, which alters the top layer of soil and undergrowth, terrestrial species like those members of the genera Brookesia in Madagascar and Rhampholeon on the mainland could potentially have their habitats ruined. Gully erosion however is much more visible and its affects are more obvious with the large craters that it creates. These problems are intensified with logging and the increasing numbers of domesticated grazing livestock in the forests.

An additional area of concern toward conserving chameleon habitat is the introduction of exotic plant species. The Malagasy Forestry Department, in a quick fix effort to counter the terrible erosion problems they were facing, planted large numbers of eucalyptus and pine trees due to their fast development. These trees have spread and have invaded many habitats. Since they do not attract insect prey for the chameleons, these areas are virtually uninhabitable by these chameleons. As the trees spread and take over, the chameleons are forced out of their habitats and the viable cites where they can live dwindle drastically. Another example is shown in West and Southwest Cameroon where many parts of the range of Ch. (T.) cristatus have been logged and rubber trees have been planted which has surely damaged the populations of this and other species of chameleon in the region.

The demise of chameleon habitat throughout their natural range is a huge problem. Without stricter management and conservation efforts, attempts at eliminating other sources of population losses will only work in the short term. For effective management and conservation, the factors damaging the chameleons in the wild must be controlled from all perspectives with special consideration to those most vital aspects. As Brady and Griffith2 wrote, "without doubt the most important factor influencing the future survival of chameleons...is habitat loss." For these reason, more effort should be placed toward helping this problem than currently allotted.

1 http://www.kenyalogy.com/eng/parques/arabuko.html - April 21, 2003.

2 Albert Earl Gilbert, pers.com. April 20, 2003.

3 Brady, L. D. & Griffith, R. A. 1999. Status Assessment of Chameleons in Madagascar. IUCN

Species Survival Commission. ICUN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.

4 Andreone, F. Conservation Aspects of the Herpetofauna of Malagasy Rain Forests. Scientific

Reports 1, Societa` Zoologica La Torbiera. Novara, Italy: 1991.

5 Jenkins, R. K. B., Brady, L. D., Bisoa, M., Rabearivony, J. & Griffiths, R. A., 2003. Forest

disturbance and river proximity influence chameleon abundance in Madagascar. Biological

Conservation, 109: 407-415.

6 Spawls, S., Howell, K., Drewes, R. & Ashe, J. A Field Guide to the Reptiles of East Africa. Natural

World Academic Press, 2002.

7 Paul Freed, pers.com. April 13, 2003.

8 Akani, G. C., Ogbalu, O. K. & Luiselli, L., 2001. Life-history and ecological distribution of

chameleons (Reptilia, Chamaeleonidae) from the rain forests of Nigeria: conservation

implications. Animal Biodiversity and Conservation, 24.2: 1-15.

9 Hódar, J. A., Pleguezuelos, J. M., & Poveda, J. C., 2000. Habitat selection of the common

chameleon (Chamaeleo chamaeleon) (L.) in an area under development in southern Spain:

implications for conservation. Biological Conservation, 94: 63-68.

Christopher V. Anderson

Chris Anderson is a herpetologist currently working on his Ph.D. at the University of South Florida after receiving his B.S. from Cornell University. He has spent time in the jungles of South East Asia, among other areas, aiding in research for publication. He has previously traveled throughout Madagascar in search of, and conducting personal research on, the chameleons of the region. He has traveled to over 35 countries, including chameleon habitat in 6. Currently, Chris is the Editor and Webmaster of the Chameleons! Online E-Zine and is studying the kinematics and morphological basis of ballistic tongue projection and tongue retraction in chameleons for his dissertation. Chris Can be emailed at Chris.Anderson@chameleonnews.com or cvanders@mail.usf.edu.

Join Our Facebook Page for Updates on New Issues:

© 2002-2014 Chameleonnews.com All rights reserved.

Reproduction in whole or part expressly forbidden without permission from the publisher. For permission, please contact the editor at editor@chameleonnews.com