Necropsy Examination

By Tom Greek, MS, DVM

Citation:

Greek, T. (2002). Necropsy Examination. Chameleons! Online E-Zine, May 2002. (http://www.chameleonnews.com/02MayGreek.html)

Introduction by the CHAMELEONS! staff:

A necropsy is the examination of a deceased chameleon. Usually, in the pet and hobbyist arena, this is done to determine the cause of death with the hopes of correcting a husbandry issue or learning what can be done in the future to prevent a similar loss. Only a qualified, experienced, person should perform a necropsy if the outcome is critical. But if a keeper does not intend to have a necropsy performed then the situation becomes a perfect opportunity for the keeper to begin to get familiar with the insides of a chameleon. Instead of disposing of the body use it as a learning experience. As Dr. Greek leads us through the major areas of the chameleon's body consider the things you can learn without a microscope. Is the chameleon eating? Are there fat reserves? Is there an infestation of parasitic worms?

Dr. Greek specializes in exotic animal care and has extensive experience with chameleons. We are very pleased to have him share a bit of that experience.

Note: All captions on pictures and below pictures are by Bill Strand with information derived from personal communication with Dr. Greek and Don Wells

It is a tragic event when we lose one of our pets. But even with the best husbandry, death is inevitable. Rather than marking it down as part of the hobby, learn from the body to help you become a better herpetoculturist.

A necropsy is the examination of a dead body, an autopsy for animals if you will. It is something that you can easily do with your reptiles with a minimum amount of equipment. Remember your high school biology frog dissection? You will essentially be doing the same thing - a systematic examination of the body and its organs. With a little experience you will be able to identify normal and abnormal organs, internal parasites, medical conditions and possible causes of death.

I encourage everyone to perform necropsies on their animals. Yet there will be times that seeking the services of a veterinarian will be warranted. Just like in human medicine, self-diagnosis and treatment may be fine for minor conditions but know when you have peaked on your own knowledge. If you are losing large numbers of animals, pets that were under the care of a veterinarian, or if you want a definitive diagnosis are all reasons to have your pet necropsied by a professional. Many times the cause of death can be determined by a gross examination of the body, other times tissue samples will be submitted to a pathologist for microscopic examination.

In all parts of the necropsy you need to know what normal looks like. With more than a hundred species of chameleons (plus any other species of herps you may be keeping) it would be impossible to cover all the subtle differences in normal anatomy. And it is also beyond the scope of this article to discuss all abnormalities you might discover. That is where experience counts so perform a necropsy on any reptile that dies, even if you know the cause of death.

Develop a systematic approach to the necropsy. I like to start by examining the body from the outside, then follow by internal organs working one organ system at a time. By doing it the same way each time, you will be more thorough.

Equipment needed is minimal. A good pair of forceps and scissors are the only things required for most chameleon necropsies. Consider latex gloves and a facemask to help prevent zoonotic diseases (diseases that may be passed from animals to humans). Common sense tells you to keep all food and drink away from your necropsy area and clean the area with a disinfectant when you are finished.

Examination of the outside of the body will be the portion of the necropsy that will be most familiar to you. Determine body condition - is the lizard thin showing that there may have been a chronic disease or fat showing a sudden onset? Are there any lumps, bumps or lesions present? Open the mouth to visualize the glottis, esophagus, teeth, jaw and the other oral structures.

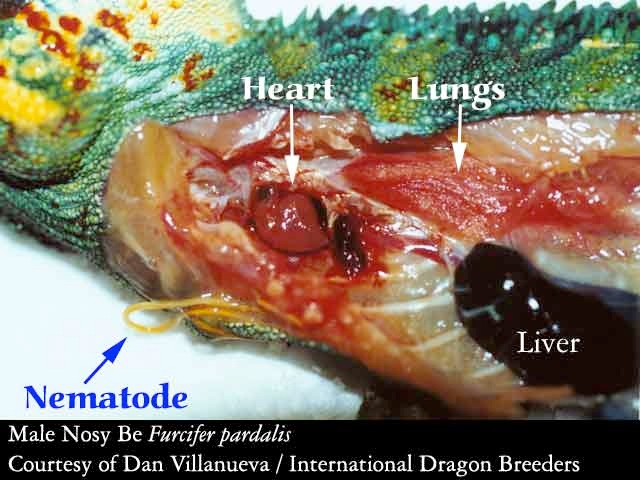

For laterally compressed species like chameleons, I lay the body on its right side. Using your scissors cut the skin along the ventral midline, then up the sides near the neck and the rear limbs creating a large flap. Be careful not to cut any internal organs in the process. Either fold the flap up or cut it off exposing the abdominal cavity. Now scan the cavity for any obvious abnormalities. You may spot large parasitic worms around the organs, large tumors, or abscesses. Most species will have some large fat pads in the caudal portion of the body. You may want to remove them to make visualization of the body organs easier.

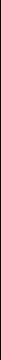

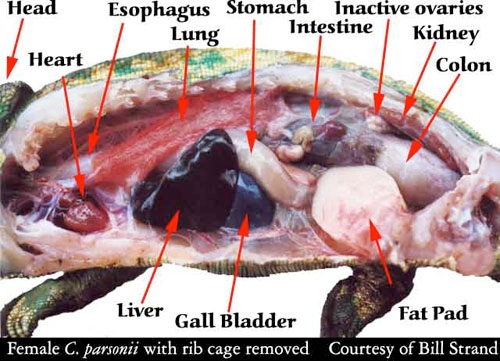

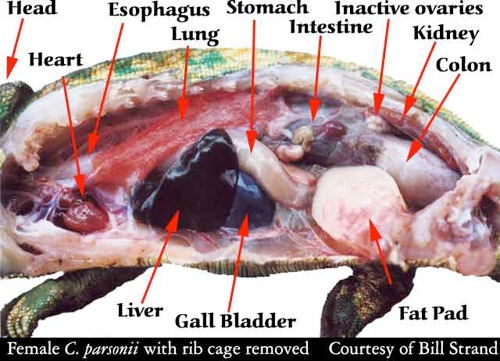

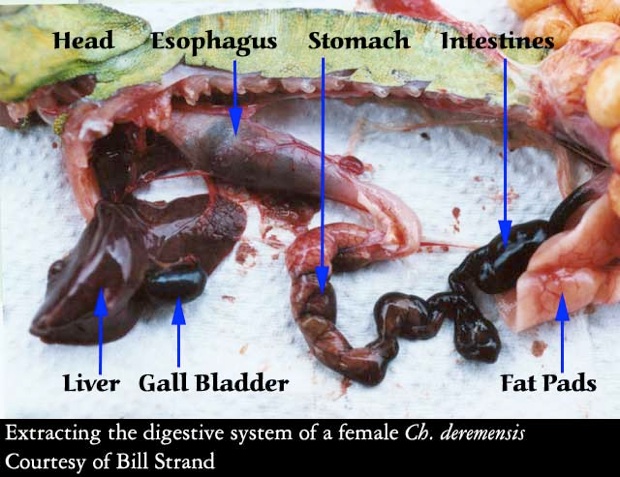

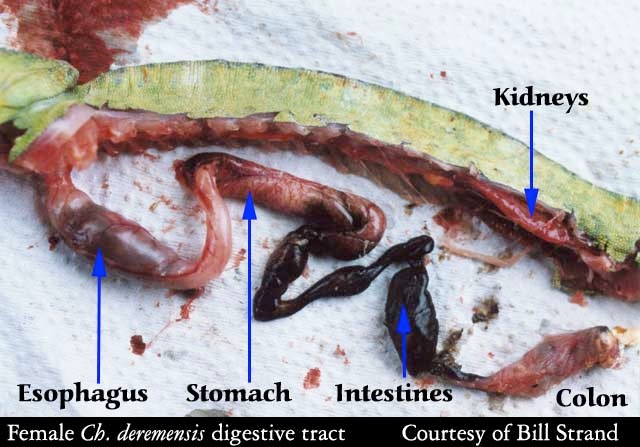

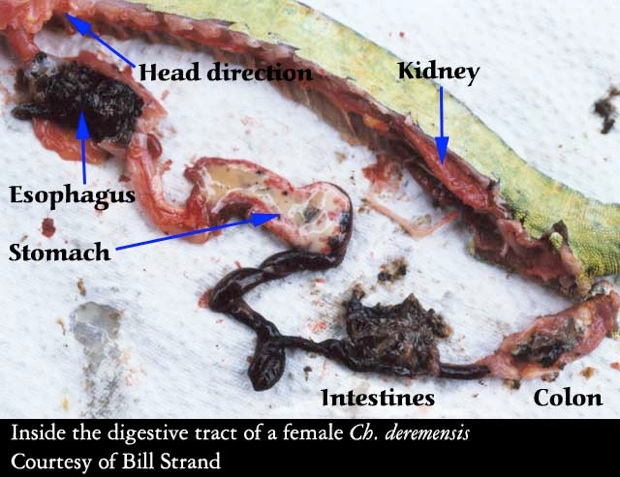

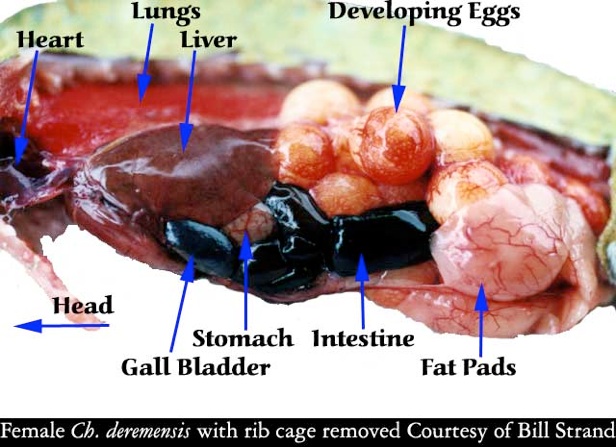

Next start with your favorite organ system. Generally I start with the digestive tract since it takes up most of the space. Start at the esophagus, then down to the stomach, through the small intestines to the colon. The liver is also part of the digestive tract. It should be firm and a uniform reddish purple color. After examining it in the body, cut the esophagus and colon and remove the organs. You can then open the stomach and intestines looking for signs of food, parasites, etc.

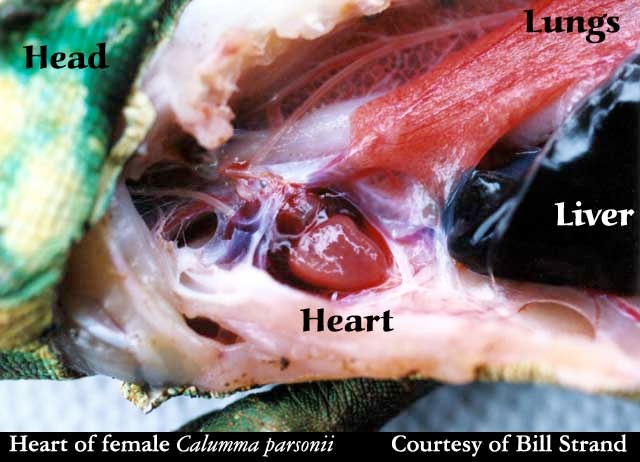

The respiratory tract is easy to locate next. The trachea and lungs are in the upper portion of the body cavity. Lungs are a reticulated sac, reddish pink in color. Large amounts of fluid or thickened dark reddish tissue are signs of disease, as are abscesses or fungal plaques.

The heart and great vessels are the only part of the cardiovascular system you will examine. The heart is surrounded with a membranous tissue called the pericardium. Between the pericardium and heart should only be a small amount of fluid. Excess fluid, thickening of the pericardium or white plaques should not be present.

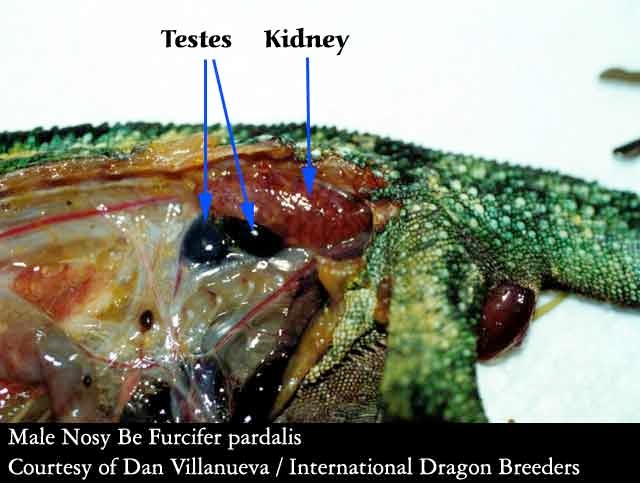

The reproductive organs are located on the mid-dorsal part of the body. Testes are usually firm, smooth and light pink to deep blue/purple in color. Ovaries will vary depending on the reproductive status of the female. They may be small with only tiny follicles present, or the follicles may be very large if the lizard was getting ready to ovulate. Ovulated eggs may be present within the oviducts.

The reptile kidney is a multilobulated reddish purple organ located along the caudal part of the abdominal cavity and may even enter the pelvic canal. Occasionally there may be some white urate crystals in the tissue but large amounts indicate disease.

You have now successfully performed a necropsy with a systematic examination of the external and internal organs. As I mentioned before, sometimes it will be very obvious what caused your pets death, other times it won't. But you won't know until you look. And what you learn may help prevent other problems in the future.

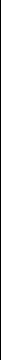

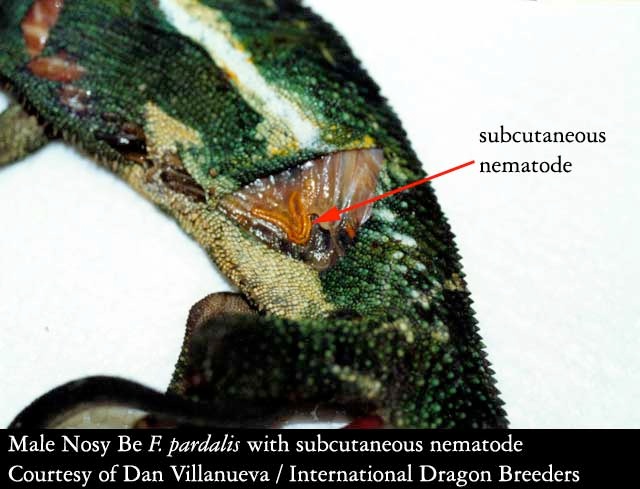

Although this female Furcifer pardalis is not dead, subcutaneous (under the skin) nematodes will maintain this appearence after death.

This picture shows the first cuts in opening up the flank of the chameleon. In this case, the person performing the necropsy wanted to view the area between the rib cage and the skin to expose the subcutaneous nematodes he could see from the outside. To accomplish this he cut only the skin and not the rib cage. To expose the internal organs the rib cage must be cut.

This view shows the outside of the rib cage. All nematodes have been removed

This picture was taken at the end of the necropsy, but is included at this point to show the infestation of subcutaneous nematodes between the opposite rib cage and the outer skin. The internal organs have been removed. The nematodes are the yellow, stringy things that can be seen when the rib cage is looked at carefully.

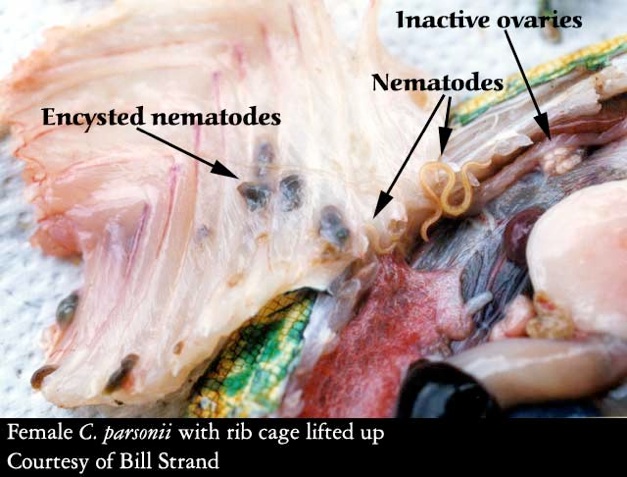

This animal had many encysted nematodes. These cysts were very hard and felt almost like rocks embedded in her flank.

Once the rib cage is folded back or removed the internal organs are exposed. After necropsying many chameleons, useful information may be gleened by the keeper. In this case, the intestines and colon are enlarged due to blockage. This bit of information is apparent to those who are familiar enough with the internal organs of a chameleon to realize that the sizes of the intestine and colon shown here are not normal. This condition was expected as it was known before necropsy that this female died of complications related to prolapse.

This trematode was found in the intestines of a female Furcifer pardalis.

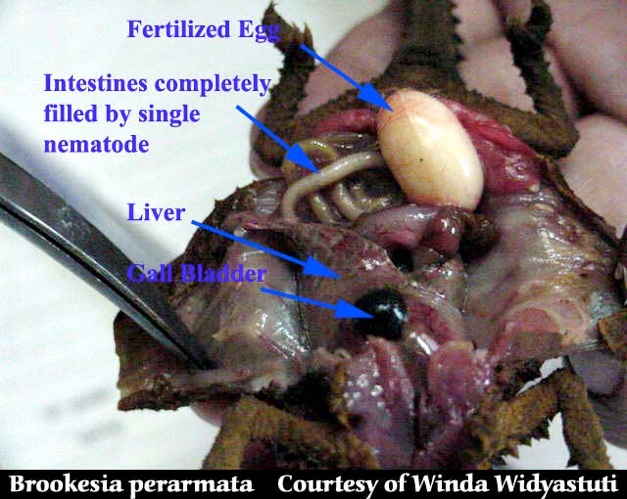

This picture shows the inside of a Brookesia perarmata. Although very small, the organs can still be viewed. This necropsy revealed a large nematode.

All the organs have been removed or pushed out of the way to show the digestive tract. Note on this animal the esophagus is filled with food material. The esophagus serves as a path for food, but not as a storage area. It is unusual to find the esophagus filled with food. The cause of death in this animal is unknown, but is suspected to be related to a fungal infection from which the chameleon was recovering.

When a chameleon chews it's food it swallows the food down the esophagus and into the stomach. The stomach breaks down the food and sends the result into the intestines where bile from the gall bladder is added to the mix. The bile helps the intestines gather the nutrients from the food soup. The end of the line is the colon which gathers the material that is to be removed from the body.

The contents of each major step in the digestive tract is shown. Look for roundworms in the stomach and intestines. Opening up the digestive tract of your chameleon also tells you what it has recently been eating and how much it has recently been eating.

The picture of the female parsonii showed inactive ovaries as clusters of small round objects by the kidneys. When the chameleon receives the correct cues, the eggs produced by these ovaries will become active and increase in size while they fill with yolk. They may do this without fertilization. This picture shows a female whose eggs have activated and developed yolks. Eggs that are not fertilized may still go through this enlargment and either be expelled as slugs or shrink back to their original size and be reabsorbed.

The shell gland, which normally is a very non-descript bit of tissue, is filled with eggs in the process of shell calcification. This picture shows how much of a female's body can be taken up during egg production!

Tom Greek, MS, DVM

Greek & Associates Veterinary Hospital

23687 Via Del Rio

Yorba Linda, CA 92887

Ph: (714) 463-1190 0r (866) 940-7028

Join Our Facebook Page for Updates on New Issues:

© 2002-2014 Chameleonnews.com All rights reserved.

Reproduction in whole or part expressly forbidden without permission from the publisher. For permission, please contact the editor at editor@chameleonnews.com