Furcifer minor - Field Study

By Christopher V. Anderson

Citation:

Anderson, C.V. (2002). Furcifer minor - Field Study. Chameleons! Online E-Zine, May 2002. (http://www.chameleonnews.com/02MayAndersonMinorField.html)

Introduction by the CHAMELEONS! staff:

Chris Anderson provides us with a personal view point from the home of Furcifer minor. His observations allow us to get a better feel for the natural habitat these animals live in. Whether this information is used in captive care or not, the information regarding populations in degraded areas and the conditions of the land is valuable in any discussion regarding the condition of wild animals in Madagascar.

Furcifer minor - Field Study

General Species Information:

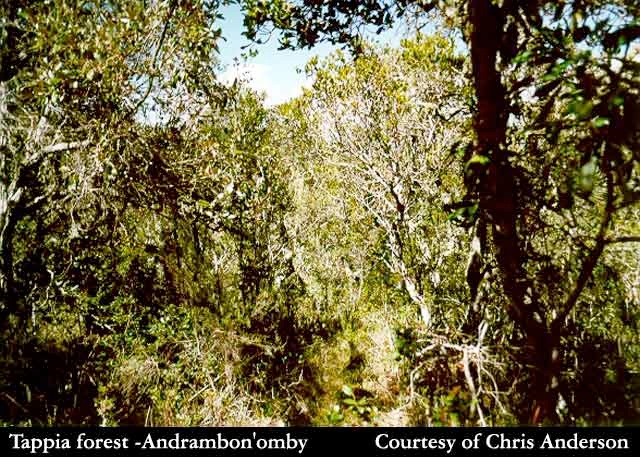

Described by Günther in 1879 from Fianarantsoa, Furcifer minor is known from a limited range around the region of Madagascar's central plateau. The areas around Ambositra and Itremo are best known for this species although other small populations in southern central Madagascar are known. The natural habitat of F. minor are the tappia forests of the region.

F. minor is a small to medium sized chameleon. Males can dwarf the females, reaching a maximum total length of up to 10 inches (25 cm) with the females reaching a maximum total length of up to 6 inches (16 cm) with a substantially visible smaller body mass. Males of this species possess a dorsal crest, which extends about a third of the way down the back. Females on the other hand, have a dorsal crest, which extends a much shorter distance down the back (often a half inch or less). The gular and ventral crests are present in both sexes, but weakly developed. Males have a double rostrum similar to that of F. bifidus or B. fischeri. This species lacks occipital lobes and scales are homogeneous.

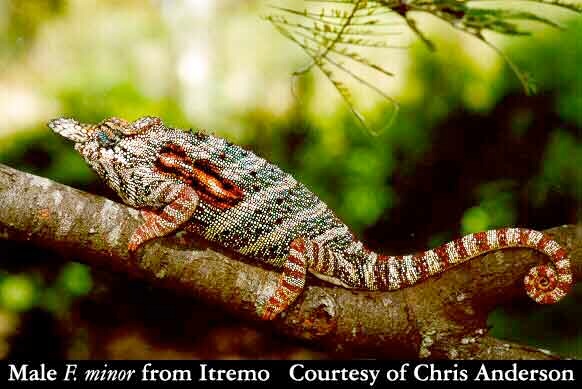

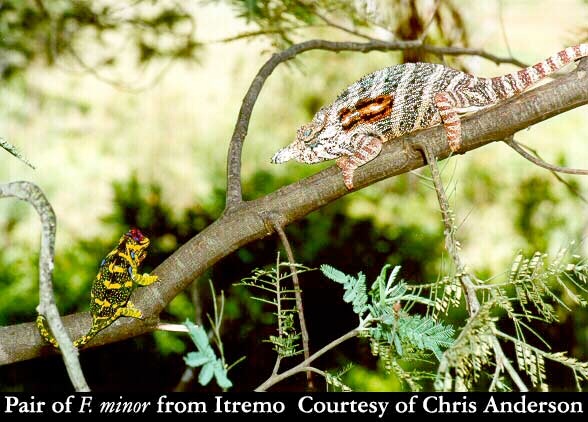

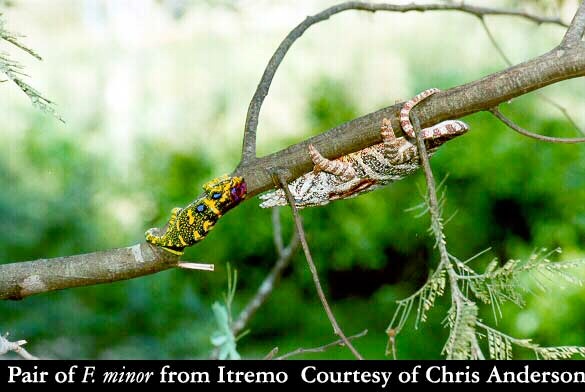

The coloration of the male F. minor is generally reddish brown with varying shades of brown, black, white and red/orange patterning. In display, male F. minor are capable of large quantities of white and black banding on the body, with red or orange bands on the limbs and tail. Additionally, the top and bottom portions of their eye turrets turn blue and two brown to whitish spots or a single elongated strip, outlined in orange and black appear on each side of the flanks toward the anterior portion. The latter two characteristics are, additionally, slightly to distinctly visible in rest colors. The author believes male F. minor to be highly underrated by most as far as appearance is concerned. This is however due to the appearance of the female which, in gravid coloration, easily contends for the position of most beautiful chameleon. In rest, the coloration the female of this species is green with slight yellowish random banding. The top of the head being red and on the anterior portion of the flanks there is two blue spots outlined in red. When gravid, the female is capable of a truly breathtaking display. The base coloration of the female becomes generally black with bright yellow speckles all over the body. The body and head also have bright yellow banding in a seemingly random order with banding on the tail. The blue spots on the flanks are intensified to a bright blue with slight red outlines. The top of the head is red, black and blue and the fully extended gular crest exposes bright red throat grooves. The female's gular and ventral crests remain very white creating a high contrast.

In Habitat Observations

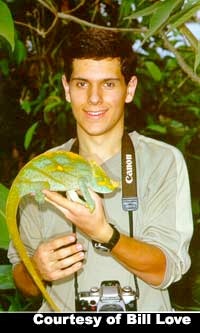

While in Madagascar in December 2001 and January 2002 with Bill Love of Blue Chameleon Ventures, we traveled from Ambositra to Itremo in hope of finding this beautiful chameleon. This was a particular goal of the author's since he is and had been working with this species in captivity. The author was unsure of what to expect as he had been informed by a number of individuals that this species was locally common while another source indicated that it was on the verge of extinction and very rare.

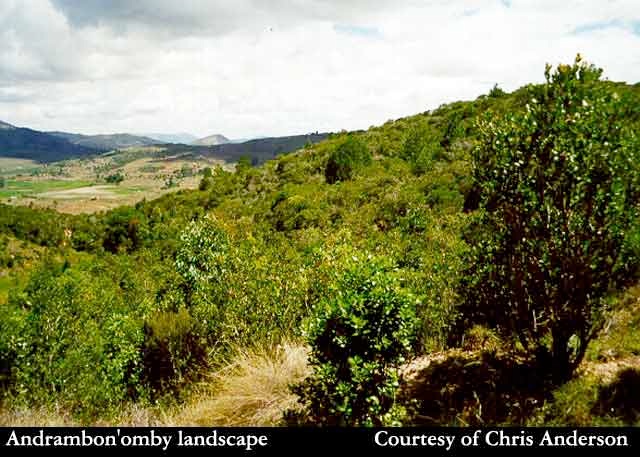

As usual, we told our driver, a Malagasy by the name of Parson, that we wanted him to stop at various locations on the way to Itremo and ask the locals to catch any chameleons they could for us. We informed them that we would be back later the day and naturally, we included instructions on the best way to keep them for us until we arrived. A mere 13km from Ambositra, Parson pulled the car over and told us that we should look here. We agreed, never being ones to deny an opportunity to look around, but curiously asked why he thought this was a good place to search. To our surprise, he informed us that this type of vegetation, which is called tappia, was the natural habitat of the species we were looking for. When we inquired as to how he gained this knowledge, he informed us that a number of years before, he had taken the well known French naturalist, Andre Peyrieras, to Itremo and that they had found specimens in that exact location, which he referred to as Andrambon'omby, an area 1 km east of Manandriana, a promising lead. We spread out in search of our query and after about five minutes heard the yells of "I've found one." We all arrived to find a beautiful young pair of F. minor. The male and female were both sub-adults of 5 inches (8 cm) total length each. The two were found three feet off the ground and within two feet of each other. After a long photo session, we were forced to move on due to time constraints. The author was very surprise by how small this patch of primary habitat was and astonished by the lack of other patches of this forest. It was also surprising that their habitat seemed to be relatively dry in comparison to where one would think this species would occur. It was also warmer and much more exposed to large amounts of sunlight than was expected. It is obvious that this species is not a typical forest chameleon.

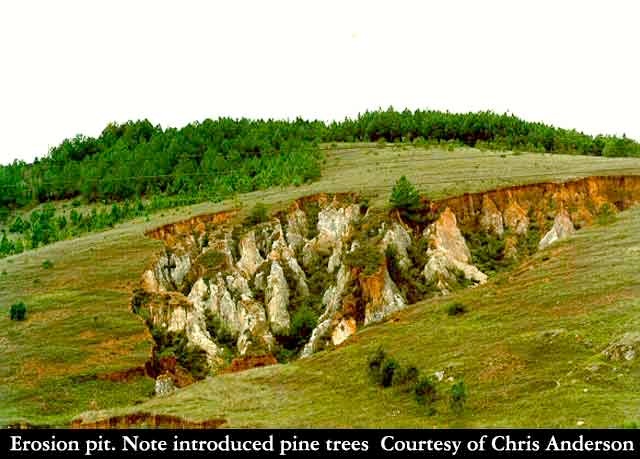

As we drove, the author was very disappointed with the condition of the land. Many portions of the habitat were virtually tree-less. The majority of the area contained concentrations of trees and bushes but of a type of distribution and concentration that one would not expect a species like F. minor to exist. Portions of the range had massive crevasses of erosion. Some of these erosion pits were easily 50-80 feet wide and at places 150 feet long. We continued and found areas that had been infested with the pests of the Malagasy landscape, Eucalyptus and pine trees, which had been planted by the Malagasy forestry department in a quick fix effort to help with replacing the deforested areas. The latter areas proved not to produce any F. minor, which is to be expected since neither attracts insects for the chameleons to feed on. Despite what we considered to be the wrong habitat for the F. minor, we continued to stop and ask the locals to collect animals for us until we reached the Itremo massif.

Once we entered the town of Itremo we asked a local boy if they ever saw any chameleons. He immediately ran off and returned almost instantaneously with a chameleon on his forearm. He had produced a robust, 9 inch (23 cm) male F. minor. Eagerly we asked him to find another. Once again he ran off to return in a remarkably short time with another chameleon. This time he produced the largest F. minor the author has ever heard of, an extraordinarily robust, bordering fat, 10.5 inch (27 cm) male F. minor. While the author proceeded to take measurements of these two specimens and start to photograph, the boy was asked if there were any chameleons around that looked any different. He replied that there were and ran off again only to return, once again quickly, with a female F. minor. This was a very healthy 5.5 inch (14 cm) gravid female. Stress needs to be placed on the surprising ease with which these specimens were found considering the state and extent of devastation in the area. The fact that this boy could so quickly locate specimens for us in a very remote town where very few foreigners go is an indicator of the success this species appears to currently be having in this highly devastated habitat.

We allowed the two males to display to each other so that we were able to get photos of their territorial display and then we proceeded to let the larger, more impressive male display to the female, which we previously were not aware was gravid. The male immediately went into the brightest coloration we had yet seen for them and started to rapidly bob his head up and down in display. The female instantaneously transformed into her gravid display and started to gape and thrust her body toward the male. As he advanced, the female, rather than retreating or even standing her ground, charged at the male with her mouth open hissing. The male retreated to the underside of the branch in reaction to her attack. The fierceness of such a small animal to another animal that is easily twice her size was remarkable. Once again, after a lengthy photo session, we were forced to leave, without much further exploration of the massif, due to time constraints.

On our return, we stopped at a number of places that we had asked to collect chameleons. A few thought we were joking and did not collect any, but some had. When we stopped in the village of Antsahakely on the way back to Ambositra, the locals had collected a total of eight chameleons for us. Antsahakely is surrounded by another barren region that we would not have expected minor to occur, so we were once again proven wrong when we saw what they had collected. One of the eight chameleons was a female F. lateralis but in addition, they had collected four male and three female F. minor. All the animals appeared very healthy although a little stressed. One male did however have a slightly stubbed tail that was well healed. The males ranged in size from 7-9 inches (18-23 cm) and the females from 4-5 inches (10-13 cm).

When we finally arrived back in Ambositra, well after dark, we had seen a total of 11 F. minor, 1 female F. oustaleti and 11 F. lateralis. While a day of research and a total of 11 specimens are hardly conclusive, F. minor appeared to be doing very well in highly disturbed habitat, at least for the time being. The ease at which and numbers that were found in highly devastated areas leads the author to suspect that F. minor is adapting or at least managing to living outside of it's natural undisturbed habitat. Additionally, with how few were located in their natural habitat, it appears as though they could even be doing better outside their primary habitat than inside it. Communication with certain individuals about this thought yielded conflicting opinions. One source said that when he went looking for this species, he did not end up going near Itremo as he found them so common in the highly degraded areas on the side of the road near Ambositra before turning toward Itremo and agreed with the author's speculation (Euan John Edwards, pers. com.). It has additionally been said that "Furcifer minor is rare in undisturbed forests but very common in degraded habitat and plantations" (Olaf Pronk, pers. com.). However, one could argue that this suggested type of punctuated evolution was impossible with the period of time since degradation, less than 1500 years, being so short by evolutionary standards. The author however feels that this argument is contestable because evolution is not what is really occurring, only adaptation, if even that. It is possible that the benefits of the degraded habitats are being utilized or are actually beneficial to the survival and reproduction of this species. Evolution does not necessarily occur when a species shows benefit to an altered habitat. One source however, believes that "the idea that any organism that evolved within [it's natural habitat] over untold millennia could somehow be equally successful in a recently created, man-made environment is ludicrous" (Todd Risley, pers. com.). The author stresses that even something as simple as fewer predators being present in the degraded area is a benefit to the chameleons and a factor that can very easily result in larger populations and increased life span. It is however clear that further degradation could quickly jeopardize the population and the fact that this species comes from such a limited range is a factor that must not be ignored. More study is necessary to conclusively determine the status of F. minor in the wild.

References:

Glaw, F. and M. Vences, A Fieldguide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of Madagascar, Second Edition. M Vences & F. Glaw Verlags GbR, Germany: 1994.

Martin, J., Masters of Disguise: A Natural History of Chameleons. Facts On File, Inc., New York, NY: 1992.

Necas, P., Chameleons: Nature's Hidden Jewels. Krieger Publishing Company, Malabar, FL: 1999.

Andrambon'omby

Itremo

Christopher V. Anderson

Chris Anderson is a herpetologist currently working on his Ph.D. at the University of South Florida after receiving his B.S. from Cornell University. He has spent time in the jungles of South East Asia, among other areas, aiding in research for publication. He has previously traveled throughout Madagascar in search of, and conducting personal research on, the chameleons of the region. He has traveled to over 35 countries, including chameleon habitat in 6. Currently, Chris is the Editor and Webmaster of the Chameleons! Online E-Zine and is studying the kinematics and morphological basis of ballistic tongue projection and tongue retraction in chameleons for his dissertation. Chris Can be emailed at Chris.Anderson@chameleonnews.com or cvanders@mail.usf.edu.

Join Our Facebook Page for Updates on New Issues:

© 2002-2014 Chameleonnews.com All rights reserved.

Reproduction in whole or part expressly forbidden without permission from the publisher. For permission, please contact the editor at editor@chameleonnews.com