Bradypodion xenorhinum

By Susan James

Citation:

James, S. (2002). Bradypodion xenorhinum. Chameleons! Online E-Zine, March 2002. (http://www.chameleonnews.com/02MarJames.html)

Introduction by the CHAMELEONS! staff:

Susan James probably has more experience with the widest variety of chameleons than anyone else. Her success with difficult species is an impressive testament to her husbandry skills. She is one who truly walks the uncharted lands of chameleon husbandry. In the process she works with chameleons few people have ever seen, much less kept in captivity.

In the year 2000, chameleons from Uganda began to be exported. One of the most anticipated species from this area was the Ugandan Rhinoceros Chameleon (Bradypodion xenorhinum). The first shipments were hugely disappointing as the animals came in very weak and dehydrated. Since then shipments have increased in quality providing opportunities for chameleon keepers to enjoy the chameleons from Uganda. From the beginning, Susan James spearheaded the effort to establish B. xenorhinum in captivity. Work with this special species has just begun. With this article, Susan gives us an update on what progress she has made in her breeding group.

Bradypodion xenorhinum

Species Background:

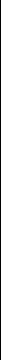

B. xenorhinum is found in the montane rainforests of the Ruwenzori Mountains of western Uganda and eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (Zaire). This exotic-looking species (even by chameleon standards) may attain a total length of up to 11 inches (28 cm) but 6-7 inches (15 - 18 cm) is more common. For additional size information on wild caught B. xenorhinum see the xenorhinum size table below.

Bradypodion xenohrinum size chart

by Euan John Edwards

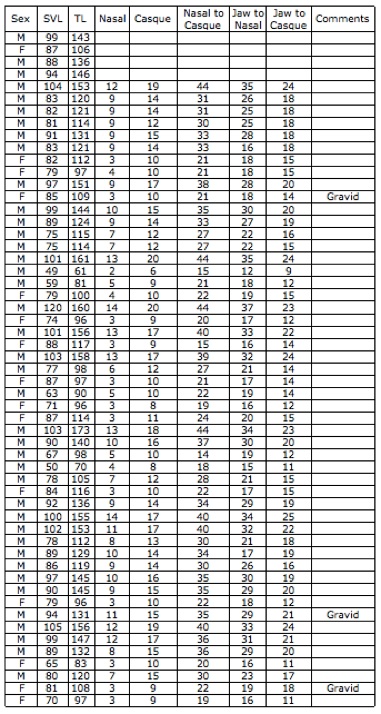

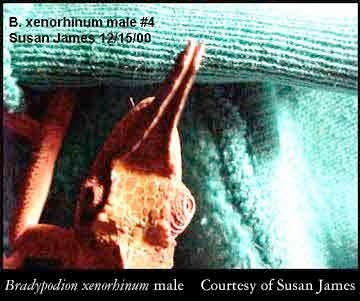

This unique animal has rarely been bred in captivity but is known to be oviparous. Males have a dramatic rostral protuberance for which this species is named. The rostral process is composed of two spatula-shaped, laterally compressed processes which bifurcate as they proceed caudally. In females, this structure is much reduced. B. xenorhinum also sports an exceptionally high casque with greatly enlarged parietal lobes but lacking occipital lobes. Scalation is heterogeneous. The head and casque are covered with enlarged, plate-like scales. Body coloration is olive green to brown. B. xenorhinum is said to have among the sharpest teeth and longest claws of any of the Chamaeleonidae (Euan John Edwards, personal communication, 2001). Males have a greatly enlarged rostral process and exhibit more olive in their basic coloration. Females are said to exhibit more brown.

Husbandry:

Any discussion of the husbandry requirements of Bradypodion xenorhinum must be prefaced by the warning that this species simply may not be well suited to captivity. Most specimens that have been through the import/export process have died. That is the bottom line. Their captive husbandry should be attempted by none but those few keepers with vast experience in chameleon (not merely reptile) husbandry. Recent imports have often arrived dead or succumbed soon after arrival. Most people experience the "drop dead overnight" problem. Eating, drinking, and defecation may be normal one day while the next morning the animal is discovered dead at the bottom of the cage. It goes without saying that a series of fecal exams is an absolute necessity for any new acquisitions.

Because B. xenorhinum is considered to be a montane species, there is a tendency to keep them in a colder environment such as might be done for Chamaeleo hoehneli. However, cold environments have not proven conducive to their health and survival and may well have contributed to the deaths of some early imports. The author has found them to do well when housed in dark-mesh screen cages during the summer in the Bay Area of northern California. The dark mesh acts as a sunscreen and provides privacy while the screen bottom provides easy drainage. The chamleons accepted temperatures of up to 100 - 105F (38- 41C) quite well as long as constant hydration was provided, as it should be for any newly acquired chameleon. During the winter these animals have been moved inside because they had become accustomed to warmer temperatures during the summer months. However, it has been difficult to find temperatures that seem to be to their liking. A 40watt bulb provides too much heat in the afternoon but if the basking light is turned off or if a lower wattage bulb is substituted they respond by climbing upside down under the fluorescent lights. Their night-time temperatures are allowed to drop into the 50s and 60s Fahrenheit (12 - 18C ). This may be a little on the cool side but they seem to be doing reasonably well and are eating well.

Hydration and humidity are best served by using a room humidifier and by a few sprayings per day. Because of the risk of respiratory infections, the keeper should avoid aiming an ultrasonic humidifier directly at the cage. In addition to being misted several times per day, each animal should also have a dripper that runs for most of the day. Eight hours per day is recommended and the animals will frequently be seen moving in and out of the water. This also permits the animal to better thermoregulate.

Recent imports are extremely finicky eaters but they may be coaxed to eat by gut loading houseflies with bee pollen so that they have yellow bellies, and coating tiny crickets with spirulina so that they have a green cast. However, once acclimated the "xenos" eat everything and anything that they can fit into their mouths. Silkworms and waxworms are their favorite foods but this may simply be due to the novelty of these foods as they are not typically offered on a daily basis. Crickets and houseflies are accepted eagerly. B. xenorhinum seems to be especially fond of newly hatched Zophobas. If necessary they will even eat fruit flies, as will most of the smaller species.

B. xenorhinum are among the most shy of all chameleons. When faced with the choice between fight and flight they will almost invariably choose flight, jumping, dropping, and even leaping from a perch. When they hit the bottom of the cage they will curl into a tight little black/brown ball and then try to burrow into whatever substrate they can find. If highly agitated they do fight and may deliver a very nasty bite for such a tiny chameleon. Of course, not every member of this species is quite this shy. A few, rare individuals may even be called 'bold'. B. xenorhinum may be hand-fed but only if the keeper is exceedingly patient and avoids eye-contact. Cage furnishings must be adapted to the shy nature of this chameleon. Thus, it is strongly recommended that there be abundant foliage and a large number of horizontal pathways to permit the animal to hide from any obtrusive human eyes.

Some xenorhinum seem to require absolute darkness to sleep. If the slightest glimmer of light is present, such as that from a digital clock or VCR, they become active. On the other hand, the few partially successful breeding attempts that have been observed have typically occurred in the dark. These considerations suggest that B. xenorhinum might be partially nocturnal, or at least strongly crepuscular. But the vast majority of breeding attempts, even by the most experienced keepers, have been unsuccessful.

The author wishes to thank Ed Pollak, Ph.D. for his editing services

References:

Klaver, C. & W. Böhme. 1997. Chamaeleonidae. Das Tierreich, 112: i-xiv 1 -85. Verlag Walter de Gruyter & Co., Berlin, New York.

Martin, J., 1992. Masters of Disguise: A Natural History of Chameleons. Facts On File, Inc., New York, NY.

Necas, P. 1999. Chameleons: Nature's Hidden Jewels. Krieger Publishing Company, Malabar, FL.

Susan James

Susan James is a co-founder of the ADCHAM web site.

Join Our Facebook Page for Updates on New Issues:

© 2002-2014 Chameleonnews.com All rights reserved.

Reproduction in whole or part expressly forbidden without permission from the publisher. For permission, please contact the editor at editor@chameleonnews.com